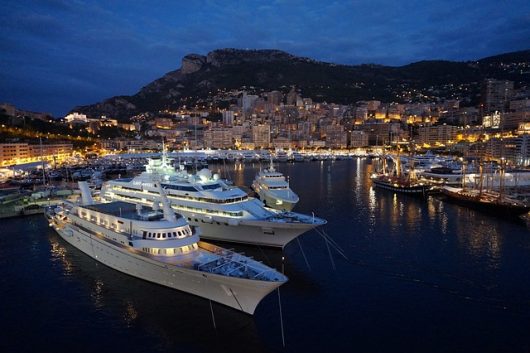

The principality of Monaco borders France on the Mediterranean Sea and draws tourists because of its casino and pleasant climate. It is 0.8 square miles and is the most densely populated country in the world and the second smallest after Vatican City. Immigrants comprise 55 percent of the total population. Tourism, banking, consumer products and much more are vital to the economy as it welcomes wealthy vacationers and residents. With the influx of people, Monaco wants to ensure economic sustainability and high quality of life while continuing to attract investors.

While Monaco is a well-established country, some of its current concerns include “managing industrial growth and tourism, environmental concerns and maintaining the quality of life.” To combat these issues, the government has created a sustainable development policy in Monaco. The plan includes reducing greenhouse gases and the effects of climate change, creating soft mobility in the city and providing aid to impoverished countries.

During the 2015 United Nations Climate Conference, Monaco announced its target of reducing greenhouse gases by 50 percent by 2030, which is about 20 percent more than the figure announced at the 2009 conference. This sustainable development policy in Monaco works together with the principality’s soft mobility initiative to “reduce traffic in the neighborhoods…whilst maintaining the development of business activity, in a space shared by all.” Monaco is also working to improve the service of city transportation and provide price incentives for drivers, buses and public parking.

The initiative of mobility is not the only aspect of the sustainable development policy in Monaco. They have also developed five flagship programs, some of which include fighting against sickle-cell disease, supporting vulnerable and street children and controlling pandemics such as malaria and HIV/AIDS. These programs are a part of the overall sustainable development policy in Monaco and support “more than 130 projects in 12 countries, primarily least developed countries (Madagascar, Mali, Burkina Faso, Niger, Mauritania, Senegal et Burundi).”

There have been great strides in moving forward with the sustainable development policy in Monaco, not just to improve their citizens’ quality of life, but the lives of children, women, the disabled, refugees and other vulnerable groups. This policy can be of benefit to millions in developing countries and a model for other nations.

– Jennifer Lightle

Photo: Flickr

Montenegro is a small Balkan country that declared independence from Serbia in 2006. Since that time, the poverty rate in Montenegro has varied rather significantly, rising as high as 11.3 percent (2006, 2012) and falling as low as 4.9 percent (2008). The most recent data available, from 2013, lists the

Montenegro is a small Balkan country that declared independence from Serbia in 2006. Since that time, the poverty rate in Montenegro has varied rather significantly, rising as high as 11.3 percent (2006, 2012) and falling as low as 4.9 percent (2008). The most recent data available, from 2013, lists the

Home to millionaires, a renowned casino and a prestigious Formula One Grand Prix,

Home to millionaires, a renowned casino and a prestigious Formula One Grand Prix,

As the

As the  The state of

The state of