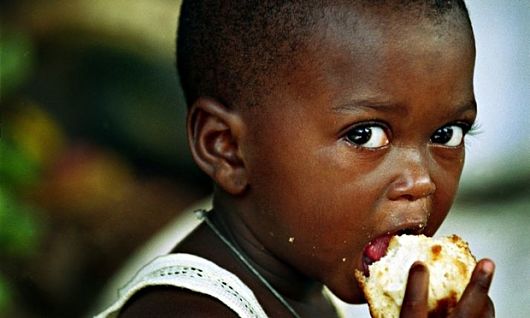

Citizens of the Republic of Burundi are plagued by malnutrition, unclean water, unsanitary conditions, poor hygiene, low quality education, food scarcity, overpopulation, sexual and gender based violence and child labor. And the question is: why is this crisis prevalent and how can everyday people help? The long-term solution to helping people in Burundi is to fix how monetary resources are allocated by its government.

Citizens of the Republic of Burundi are plagued by malnutrition, unclean water, unsanitary conditions, poor hygiene, low quality education, food scarcity, overpopulation, sexual and gender based violence and child labor. And the question is: why is this crisis prevalent and how can everyday people help? The long-term solution to helping people in Burundi is to fix how monetary resources are allocated by its government.

Seeing as that task is daunting for the layman, the following paragraphs provide information on how to help people in Burundi.

Helping people in Burundi is frankly, difficult. This is because the European Union, Belgium, United States and other western countries have decided to suspend all bilateral aid (when one country’s government gives financial aid to another’s country’s government) to Burundi’s government because of human rights violations and an unwillingness to engage in sincere negotiations for peace.

Prior to the freeze, bilateral aid accounted for about half of Burundi’s overall budget. Lack of bilateral aid will only further hurt the country’s economy, and Burundi’s economy was already one of the least developed in the world.

While bilateral aid has been suspended, humanitarian aid has not. Here are three humanitarian organizations you can donate to in order to help people in Burundi:

1. World Food Programme

People in Burundi need food. The World Food Programme (WFP), the leading humanitarian organization fighting hunger worldwide to help them get that food, needs donations. In Burundi, only 28 percent of the population are food-secure and as many as 58 percent are chronically malnourished. WFP provides hot meals to primary school aged children in food insecure areas to encourage school attendance. Two hundred thousand children currently receive assistance from this program.

WFP also offers food assistance to 70,000 pregnant and nursing women who are underweight 6 months before birth and for up to 3 months after birthing. In addition, WFP provides food to refugees and people living with HIV and AIDS. Finally, WFP teaches locals in Burundi how to be more efficient in agriculture through its Food-for-Training/Food for Assets program.

Three hundred and fifty thousand people are being taught infrastructure development, how to rehabilitate deforested areas, agro-forestry and micro-economic training.

2. BeyGOOD

People in Burundi need access to clean water. Donate to Beyonce’s organization, BeyGOOD. BeyGOOD is working with UNICEF to supply safe water to people in Burundi. A statement on Beyonce’s website states: “With your help, nearly half a million people will gain access to safe water, as BEYGOOD4BURUNDI and UNICEF will support building water supply systems for healthcare facilities and schools, and the drilling of boreholes, wells and springs to bring safe water to districts.”

Donation gifts range from $3.11 for a collapsible 68-ounce water container for one person to $1,430.06 for a water tank kit for 1,000 people.

3. The Burundi Education Fund

People in Burundi need better quality education. Poverty and hunger have made it difficult for students to obtain an education. After the 6th grade, the Burundi Educational System simply does not have the room or resources to place children in schools. This results in students having to compete to be selected for the next grade by taking difficult placement tests. In some cases even if the student passes the test, he or she cannot move further in education due to the inability to afford tuition fees or school supplies.

The Burundi Education Fund, Inc. is a charitable Christian organization formed to provide materials and financial support to students and schools in extreme poverty in Burundi, Africa.

Specific successes of the organization that have helped students obtain their education include building a 26-bed dormitory safe house for the girls of Muramba High School, a running water fountain that provides clean drinking water to more than 1,900 students in the Mubimbi district and supporting a transfer student program.

The highly selective transfer program offers high school students a chance to continue their education in the U.S.

These are the most vital examples on how to help people in Burundi. The organizations above are addressing key needs of Burundian people’s lives that help them to obtain their basic human rights. While helping the people of Burundi may seem daunting, to be a responsible global citizen one must not turn a blind eye to tactics that can help others improve their quality of life.

Take action today and help one of the world’s poorest and hungriest nations become food and wealth secure.

– Jeanine Thomas

Photo: Flickr

Since the political upheaval of Burundi’s 2015 elections, the Imbonerakure, the youth wing of the ruling party, continues to pose a direct threat toward

Since the political upheaval of Burundi’s 2015 elections, the Imbonerakure, the youth wing of the ruling party, continues to pose a direct threat toward  Burundi is a landlocked nation

Burundi is a landlocked nation

Populated with over 10 million people,

Populated with over 10 million people,