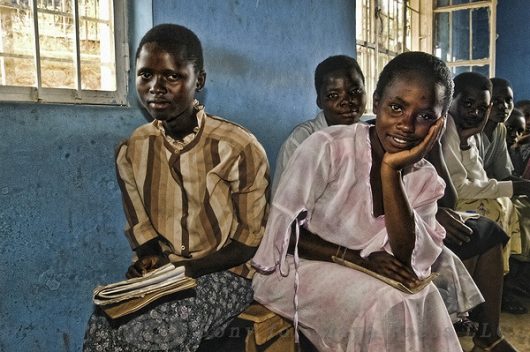

Quality education is the cornerstone of a prosperous nation. But in Cameroon — an ethnically diverse country in south-central Africa — only 53 percent of children attend secondary school. Also, the state of girls’ education in Cameroon is troubling since they do not have access to quality education and many of them are not even enrolled in schools. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 70 percent of Cameroonian girls are illiterate.

Quality education is the cornerstone of a prosperous nation. But in Cameroon — an ethnically diverse country in south-central Africa — only 53 percent of children attend secondary school. Also, the state of girls’ education in Cameroon is troubling since they do not have access to quality education and many of them are not even enrolled in schools. According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics, 70 percent of Cameroonian girls are illiterate.

Facts about Girls’ Education in Cameroon

A variety of factors influence the lack of education among girls in Cameroon. Traditional values stifle chances of prolonged schooling or any schooling for girls. Poverty often forces women to leave school and to work and earn an income for their families. In addition, high rates of youth pregnancy and child marriage impede continued education for many girls. Although Cameroon ratified the 1989 United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child which sets the minimum age of marriage at the start of adulthood, yhe legal age of marriage in the country is still 15 with parental permission. In 2014, the UNICEF found that over 31 percent of teenage girls in Cameroon were married before age 18.

Patriarchal norms drive down girls’ education in Cameroon as well. Patience Fielding from the University of California, Berkeley found that women’s educational pursuits are further restricted in higher educational institutions as well, especially in the fields of math, science and technology. Even as girls struggle to enroll in schools, obstacles meet them in the classroom. Girls face a disproportionate amount of discrimination, sexual harassment and violence.

What’s Happening

Nelson Mandela once said, “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world”.

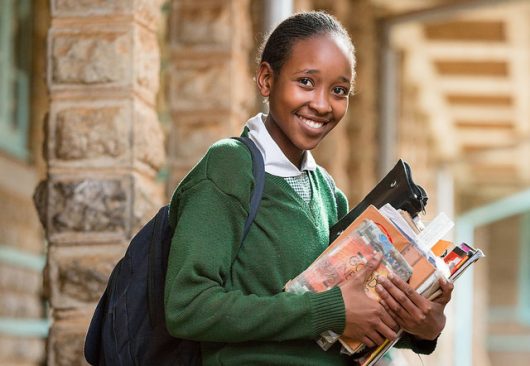

International organizations are supporting Cameroonian girls and increasing female enrollment in schools. UNICEF works to advocate early childhood education as well as supply resources and classroom materials to students and teachers.

Cameroonian women are also spearheading efforts to make social change and promote girls’ education in Cameroon. In a 2016 Times article, Leila Kigha talks about her grandmother’s efforts to inspire other Cameroonian women and the ripple effect a single woman’s hope for the future can have on others. She refused to accept the status quo and sent her children to school against all odds. Her descendants went on to establish the Shine A Light Africa initiative — a nonprofit that works to allow women to sell farm products in groups.

This work has been monumental in ensuring that change happens. Research shows the positive externalities resulting from girls having access to better and continued education consequently leading to a higher standard of living. In addition, improving girls’ education can reduce maternal death and infant mortality rates substantially.

Conclusion

The Republic of Cameroon’s constitution outlines that the State shall guarantee a child’s right to education. However, equal and prolonged access to education is often not a reality for Cameroonian girls. Thus, it requires international attention from political leaders and focused agendas to help reduce the gender gap in education to greatly influence individual lives in such nations.

– Isabel Bysiewicz

Photo: Flickr