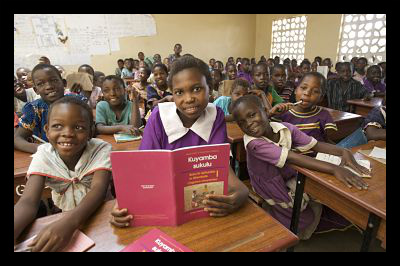

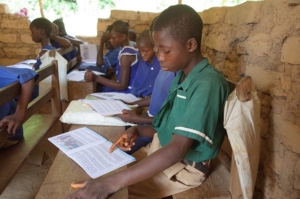

There have been huge gains in global education recently. Schools have been built, enrollment numbers have soared and equality has risen. While much of the focus has been on these factors – schools and teachers – there is another that needs more attention.

Teachers. Love or hate them, they are key to education anywhere. But there is a problem associated with them in the developing world: there are not enough of them in many places. Ninety-three countries around the world do not have enough teachers. United Nations estimates suggested that the world needed four million teachers by this year in order to meet the 2015 Millennium Development Goal of primary education for all. Of this four million, 2.6 million were needed to replace teachers either retiring from or quitting the profession.

Even more teachers will be needed for the next round of development targets set for 2030. Up to 27 million teachers are needed to meet the goal of universal primary education for all by 2030. India alone will require three million new teachers and Sub-Saharan Africa will need 6.2 million.

One issue that comes with the need for more teachers, is that for every teacher trained and put to work, more children are born. This is especially true in Africa, where many country’s populations are expected to explode if they are not already. For every 100 primary school-aged children in 2012, there will be 147 in 2030. This is why out of the 6.2 million new teachers needed, 2.3 million will be completely new positions at schools around Africa. This presents another problem: to pay for all these new teachers, $5.2 billion will be needed for their salaries.

Fueled by desperation for more teachers, many countries fail to train their teachers to the required standards. One in three countries with data available shows “less than 75 percent of primary school teachers were trained according to national standards; and less than 50 percent in Angola, Benin, Equatorial Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Senegal and South Sudan.” This means that for every one trained teacher in Chad, there are 101 students. In the Central African Republic, the ratio is even worse: 138 students for every trained teacher

It could be said that simply training teachers and putting them into school is not actually that daunting of a task. But the real issue at the root of the global teacher shortage is the rate that teachers are leaving the profession. Teaching in the developing world, where survival comes before everything, the pay is not enough. It is for this reason that 24 of the 28 million teachers needed by 2030 will serve to replace other teachers leaving the profession for.

To combat this, countries are trying a whole range of different tactics. In Indonesia and Benin, the governments have raised teachers to civil service status, and in Korea seasoned teachers are enticed to stay with salaries more than double what new teachers make.

Addressing the global teacher shortage is extremely important in the fight against poverty. Education is a gateway out of destitution, but more properly trained teachers are essential for this to be true. “An education system is only as good as its teachers.”

– Greg Baker

Sources: Worldwide Learn, BBC, The Guardian, UNESCO

Photo: The Recruiting Times

The number of children across the globe attending primary school at the beginning of the 1800s: 2.3 million. This number has surged to 700 million today. But despite this gigantic increase, primary school children across the developing world still face one major problem: a global education gap between developed and developing countries.

The number of children across the globe attending primary school at the beginning of the 1800s: 2.3 million. This number has surged to 700 million today. But despite this gigantic increase, primary school children across the developing world still face one major problem: a global education gap between developed and developing countries.

Education in

Education in