Joining the fight to tackle period poverty in the Dominican Republic, Batey Relief Alliance, a nonprofit organization in the Dominican Republic, worked with Always, a famous American brand of menstrual products, to distribute pads to Dominican women through their #ChicaAyudaChica campaign.

Joining the fight to tackle period poverty in the Dominican Republic, Batey Relief Alliance, a nonprofit organization in the Dominican Republic, worked with Always, a famous American brand of menstrual products, to distribute pads to Dominican women through their #ChicaAyudaChica campaign.

Period Poverty and its Effects

According to UNFPA, “period poverty describes the struggle many low-income women and girls face while trying to afford menstrual products.” Though period poverty is a global issue, it is more prevalent in countries where women are disproportionately impacted by economic hardship. In the Dominican Republic, while the poverty rate is 3% higher for women compared to men, it is also important to note that “40% of women [carry] out unpaid work at home.”

Societal norms limit many Dominican women to domestic work rather than professional occupations. Women in rural Dominican Republic who do work often earn a total of $1 per day when the average package of pads costs $3, making it near impossible for them to afford the products. Thus, the cycle of period poverty persists.

Along with financial difficulties, women also struggled to access menstrual products due to COVID-19, as shown in a survey conducted in 30 countries including the Dominican Republic. Per the survey, 73% of health professionals noted that increased shortages and disrupted supply chains restricted women from buying menstrual products. In addition, 68% of health professionals highlighted that there was limited access to “facilities to change, clean and dispose of period products.”

Without access to sanitary products, most girls fear they will bleed through their clothing and be seen as “unclean” or “dirty” due to the taboo placed around periods and sexual health. In response, some girls trade sexual favors for money to pay for their menstrual products, while others simply stay home from school. These absences lead to lasting negative effects as these girls sometimes miss out on their education or drop out altogether.

How Batey Relief Alliance is Helping Dominican Women

Batey Relief Alliance is a non-political nonprofit founded in 1997 that addresses extreme poverty for women, children and families across the Americas and the Caribbean. In 2021, the organization revealed that 20% of Dominican girls in rural areas missed an average of 2-3 days of school monthly due to lack of access to menstrual products. Overall, a UNICEF report notes that only 56.7% of Dominican girls complete high school.

In response to period poverty in the Dominican Republic, the organization partnered with Always and a famous supermarket chain in the Dominican Republic called La Sirena to launch the ChicaAyudaChica campaign on April 6, 2022. The ChicaAyudaChica, or GirlHelpsGirl campaign is a response to the financial strain the pandemic placed on low-income families. The initiative grew using platforms like Twitter and Facebook to reach a bigger audience. By the end of the month, Always donated 20,000 sanitary pads to girls who lived in the rural province of Monte Plata, the seventh poorest town in the Dominican Republic.

Moving Forward

Even though the campaign is over, Always continues the fight against period poverty through its ongoing #EndPeriodPoverty movement, using social media as a tool to spread the word. As awareness of period poverty and its effects increases, the more young girls and women can gain control over their well-being and future economic opportunities.

– Blanly Rodriguez

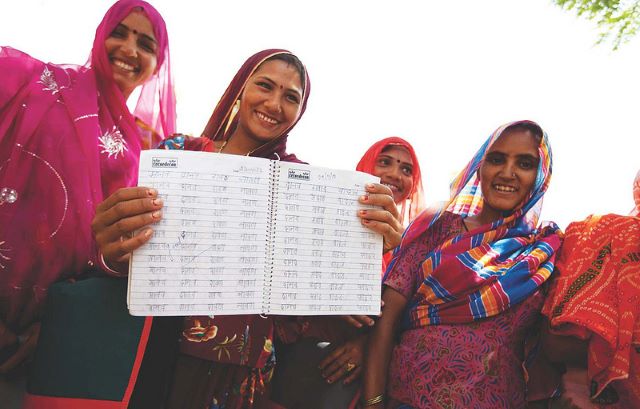

Photo: Flickr

Period poverty means a woman or girl is unable to afford sanitary products to properly manage menstruation. In 2017, research showed that a

Period poverty means a woman or girl is unable to afford sanitary products to properly manage menstruation. In 2017, research showed that a  On November 24, 2020, a groundbreaking moment occurred that changed the struggle against period poverty. The Scottish Parliament passed the

On November 24, 2020, a groundbreaking moment occurred that changed the struggle against period poverty. The Scottish Parliament passed the  Period poverty in Guatemala weighs heavily on the country’s women and girls. The lack of access to hygiene management education and proper sanitation tools forces young girls out of school for days at a time. As young girls grow up in Guatemala, they are met with a challenge. Specifically, their menstruation cycle. Not only is this a milestone in their personal lives but also a limitation. The lack of access to necessary feminine products forces girls to stay home for days. However, as technology evolves and resources are found, many organizations are working to end period poverty in Guatemala and beyond.

Period poverty in Guatemala weighs heavily on the country’s women and girls. The lack of access to hygiene management education and proper sanitation tools forces young girls out of school for days at a time. As young girls grow up in Guatemala, they are met with a challenge. Specifically, their menstruation cycle. Not only is this a milestone in their personal lives but also a limitation. The lack of access to necessary feminine products forces girls to stay home for days. However, as technology evolves and resources are found, many organizations are working to end period poverty in Guatemala and beyond. Pakistan, a country in South Asia, has the world’s fifth-largest population and spans more than 800,000 square kilometers. Pakistan has a

Pakistan, a country in South Asia, has the world’s fifth-largest population and spans more than 800,000 square kilometers. Pakistan has a  Globally, women are faced with the invisible burdens of gender inequality which are entrenched deeply within institutional structures and communities as a whole. These prejudices may limit a woman’s access to higher employment and assistance programs, ultimately leading to higher rates of poverty, especially among women of color. As of 2018, the

Globally, women are faced with the invisible burdens of gender inequality which are entrenched deeply within institutional structures and communities as a whole. These prejudices may limit a woman’s access to higher employment and assistance programs, ultimately leading to higher rates of poverty, especially among women of color. As of 2018, the  Millions of women and girls around the globe are affected by

Millions of women and girls around the globe are affected by  Thailand’s taxation of menstrual products has contributed to period poverty in Thailand. Pads and tampons have a 7% value-added tax. If a Thai woman earning minimum wage uses five pads a day, she spends more than 12% of her daily salary on menstrual care. Many working-class women experience period poverty in Thailand, which means their income is too low for menstrual care.

Thailand’s taxation of menstrual products has contributed to period poverty in Thailand. Pads and tampons have a 7% value-added tax. If a Thai woman earning minimum wage uses five pads a day, she spends more than 12% of her daily salary on menstrual care. Many working-class women experience period poverty in Thailand, which means their income is too low for menstrual care. Menstruation is a natural and essential part of human life. For women facing period poverty in Tanzania, lack of access to menstrual management products and sanitation facilities can result in lost opportunities for work or education.

Menstruation is a natural and essential part of human life. For women facing period poverty in Tanzania, lack of access to menstrual management products and sanitation facilities can result in lost opportunities for work or education.