Democratization in Burma, now Myanmar, seems to have opened up a can of worms. Freeing political prisoners, allowing freedom of speech, granting access to social media and tolerating freedom of assembly has allowed many Burmese people to express what had long be suppressed, albeit incompetently at times – a deep-seated hatred for the Rohingya Muslim minority.

The Rohingya make up five percent of Buddhist-majority Myanmar and have been discriminated against for centuries. They are denied citizenship and many basic rights because they are not seen as Burmese, even though their families were brought over from what was then Bengal many generations ago. But while the military junta was in power, it jailed anyone who incited violence against the Rohingya in the interest of keeping peace.

In 2011, the regime finally started opening up and passed a series of political, economic and social reforms. Among other developments, Myanmar freed opposing politician Aung San Suu Kyi after placing her under house arrest for fifteen years. It also gave general amnesty to hundreds of political prisoners, one of which was a monk named Ashin Wirathu.

Wirathu had been jailed for twenty-five years for inciting anti-Muslim hatred. Now free to resume his activities, Wirathu helped instigate a wave of resentment toward the Rohingya that cumulated in the deadly 2012 Rakhine State riots and the 2013 nationwide anti-Muslim riots. He now heads the fanatic 969 movement, which has a large following among the Buddhist population.

The movement calls on all Buddhists to refuse to do business with the Rohingya and demarcate their homes and businesses using the “969” sticker. They are already pervasive on many shop windows, cars and motorbikes across Myanmar. The economic boycott against Muslims is only one of the four propositions of 969; the others are to restrict marriage between Buddhists and Muslims, forbid religious conversions and prohibit polygamy.

The general intent of these laws, according to Wirathu, is to prevent a much-feared Muslim “population explosion.” He calls Muslims “African carp” that “breed quickly and eat their own kind.” The Rohingya, he claims, are a threat to Buddhism and the Burmese national identity.

The movement has already succeeded in getting a “population control” bill signed into law. The bill gives the government the power to stop mothers from having another child for 36 months. Human rights groups are certain that this law will only victimize Rohingya women.

These racist attitudes are not marginal, according to Richard Horsey, a political analyst from Yangon. In fact, these extremist views are mainstream. Matt Smith, executive director of Fortify Rights, said that people often get together in community meetings similar to American town hall meetings to discuss how to get rid of the “Bengali problem.” In Karen State, host to Myanmar’s capital Hpa-an, fliers exhort people to stop Muslims from leasing homes and farms, and some threaten Buddhists who act as their middlemen.

Facebook, which had long been suppressed under the junta regime, is now also being used as a means to spread hatred. Users encourage their friends and family members to support the 969 movement. Groups such as the “Kalar Beheading Gang” (“Kalar” is a highly derogatory word given to Muslims) have popped up.

Attacking the Rohingya has therefore become good politics in Myanmar, Jonathan Head, the BBC correspondent for Southeast Asia, asserts, and rhetoric is heating up as elections approach in November. Fear mongering has allowed new and rising politicians to curry favor with the Buddhist majority. Aung San Suu Kyi, once seen as the symbol of human rights in the country, and now head of the National League for Democracy Party, has been conspicuously silent.

The Rohingya were also recently stripped of their right to vote. Just before the end of military rule in 2008, the junta had allowed them to vote and even put up candidates for election. But in 2013, when the government said it would maintain the Rohingya’s right to vote in a constitutional referendum, Buddhists staged massive protests. Hoping to appease the population, the government made the Rohingya turn in their identity cards.

Many international organizations have said that the recent events amount to genocide. More than 170,000 Rohingya live in internally displaced persons camps throughout the country after their houses and villages were burned to the ground in riots. They are circled by hostile Buddhist populations that do not allow them to leave the camp. The camps rarely have medical facilities and the Rohingya often have to sell their meager food rations to obtain medicines for their children. Jonathan Head calls the conditions “ghetto-like.” The government has actively refused to count casualty rates.

During a recent international conference in Norway that aimed to address the Rohingya crisis, George Soros, a business magnate turned philanthropist, said that “In 1944, as a Jew in Budapest, I, too, was a Rohingya…Much like the Jewish ghettos set up by the Nazis in eastern Europe during World War II, Aung Mingalar has become the involuntary home of thousands of families who once had access to healthcare, education and employment. Now they are forced to remain segregated in a state of abject deprivation. The parallels to the Nazi genocide are alarming.”

More than 150,000 Rohingya have fled Myanmar in overstuffed and rickety boats within the last three and a half years of democratic reforms. Smugglers promise to take them to Malaysia or Indonesia, Muslim majority countries. Jonathan Head voiced concern over the appalling conditions of the boats, which he said “were akin to the 18th century slave trade.” People cannot stand or sit properly, and are beaten if they try to stretch their legs. They are given a cup of rice, a single chili and two cups of water a day until the food runs out, as it often does.

Many boats never reach their destination and are instead handed over to traffickers, usually in Thailand, where people are then held ransom for up to $2,000. This often means that relatives in Myanmar have to sell their remaining land and homes to get them out. If they cannot, the traffickers simply leave them to starve. Recently, mass graves were uncovered in Thailand and Malaysia.

Myanmar refuses to admit responsibility for the crisis. Major Zaw Htay, director of the President’s Office, said that the country would “not accept allegations by some that Myanmar is the source of the problem.”

— Radhika Singh

Sources: Bangkok Post 1, Bangkok Post 2, Foreign Correspondants Club of Thailand, Bangkok Post 3, Al Jazeera, Asia Nikkei, Global Post 1, The Guardian, Global Post 2, BBC

Photo: Flickr

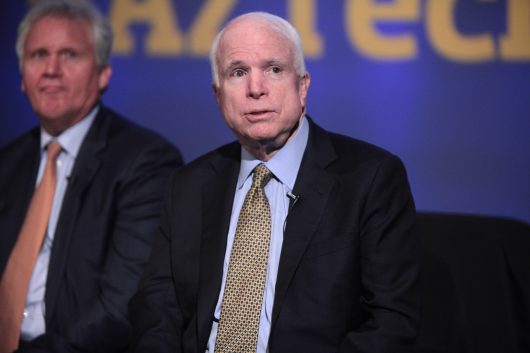

The Burma Human Rights and Freedom Act of 2017, a bill focused on promoting democracy and human rights in Burma, was recently introduced in the United States Senate.

The Burma Human Rights and Freedom Act of 2017, a bill focused on promoting democracy and human rights in Burma, was recently introduced in the United States Senate. On September 12, 2017, Arizona Senator John McCain spoke out against the treatment of the Rohingya population of Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. The Rohingya people are mostly Muslim-practicing individuals, and according to the United Nations, they are under attack. Specifically, the U.N. stated that the situation, which is characterized by a series of “cruel military operations,” is a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. Thus, the ethnic cleansing in Myanmar must not be ignored.

On September 12, 2017, Arizona Senator John McCain spoke out against the treatment of the Rohingya population of Myanmar, formerly known as Burma. The Rohingya people are mostly Muslim-practicing individuals, and according to the United Nations, they are under attack. Specifically, the U.N. stated that the situation, which is characterized by a series of “cruel military operations,” is a “textbook example of ethnic cleansing”. Thus, the ethnic cleansing in Myanmar must not be ignored. As a minority group, Rohingya Muslims have been subjected to violence throughout the entirety of their existence. In what is being called “ethnic cleansing” and “genocide”, more than

As a minority group, Rohingya Muslims have been subjected to violence throughout the entirety of their existence. In what is being called “ethnic cleansing” and “genocide”, more than