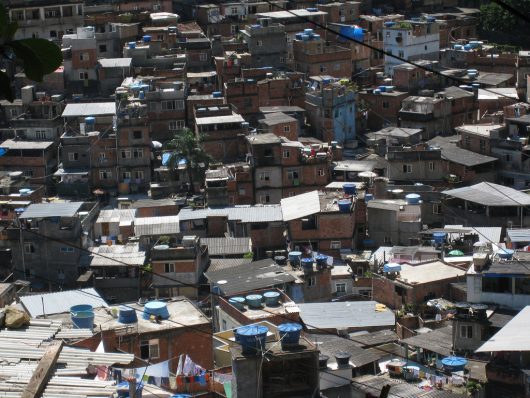

Sao Paulo is, by far, Brazil and Latin America’s largest city. The urban population is about 12 million, not including the metropolitan region right outside of Sao Paulo that accounts for about 20 million people. Despite the fact that the city’s commerce accounts for more than 12 percent of Brazil’s total GDP, close to a third of Sao Paulo’s 12 million people live in slum-like conditions.

The combinations of favelas and irregular land subdivisions are glaring symbols of Sao Paulo’s lingering poverty and tremendous inequality; however, while the conditions of Sao Paulo have worsened over the years, there have been some signs of structural improvement. Here are the top 10 facts about poverty in Sao Paulo.

Top 10 Facts About Poverty in Sao Paulo

- Sao Paulo is known as the largest city in the Western Hemisphere and has a poverty rate of 19 percent.

- Sao Paulo has a significant income gap between the rich and the poor. In 2000, a study conducted by Sao Paulo University found that half of the state’s population earned only 15 percent of the total income of the state.

- Sao Paulo has a gap between skilled workers needed in an industrialized and rapidly growing economy and limited skills available in the workforce. Brazilian employers and companies face increasing competition for skilled workers that limit the opportunities for growth.

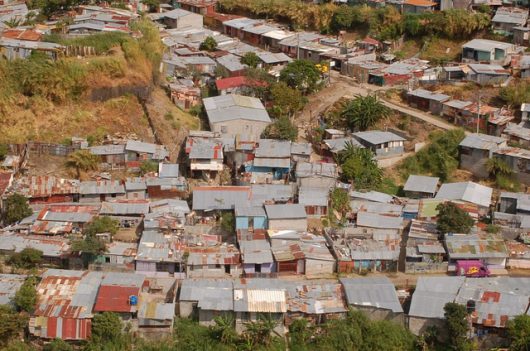

- Sao Paulo struggles with the housing shortage in which about 1.2 million people live in urban favelas or corticos. Favelas are private or public lands that began as temporary squatter settlements. Corticos are abandoned buildings that are illegally occupied and are typically in precarious states of repair.

- Residents in Sao Paulo’s second biggest slum, Paraisopolis (which literally translates to Paradise City), have expressed a strong desire to stay rather than be relocated. This resistance has inspired official Brazilian policy to shift towards slum upgrading rather than slum eradication. Slum upgrading proves to be easier, cheaper, and not to mention, more humane.

- One of Sao Paulo’s major goals was to bring electricity, effective sanitation and clean water services to as many urban areas as it could afford; now, almost all favelas have access to clean water services and electricity.

- While Paulistanos generally have adequate access to water resources, the water supply system loses about 30 percent of water in distribution.

- In 2006, the Sao Paulo Municipal Housing Secretariat created an information database system with the ability to track the developmental statuses of favelas and other precarious settlements. This system allows for the effective targeting of slum upgrade efforts and environmental cleanups.

- Transportation issues are amongst the most noticeable signs of Sao Paulo’s difficult infrastructure. The average Paulistano spends about 2 hours per day in traffic jams which costs the city about $23 billion a year. On the other hand, public transportation is notoriously overpriced, overcrowded and uncomfortable.

- Government corruption is also known to be a major contributor to the slum-like conditions in Sao Paulo. Frustration with the government’s unmet urban needs have even resulted in protests; however, rather than a source of concern, these protests may be a sign of progress. Local and national governments have responded with efforts to promote transparency of government spending as a a result of these demonstrations.

Favela Reduction

While there have been tremendous efforts towards upgrading the favelas in Sao Paulo, these areas still have a long ways to go. It is extremely necessary for a collective promotion for the inclusion of both local community leaders and government agencies so as to effectively reduce the number of favelas in Sao Paulo.

– Lolontika Hoque

Photo: Flickr

In 2010 the

In 2010 the