Since the start of the new year, Sudan has received a flurry of media attention. What started as students protesting rising wheat prices escalated into civil unrest quickly spread across the country as thousands of activists call for President Omar al-Bashir’s resignation. The government’s response has received widespread condemnation, with Amnesty International reporting the death of 40 protestors and thousands of arrests.

The unrest sweeping through Sudan is complex, rooted in social, political and economic instability. For decades, living conditions across this African nation have fostered an environment that leaves behind vulnerable citizens and perpetuates poverty. The following top 10 facts about living conditions in Sudan are intended to unpack these factors.

Top 10 Facts About Living Conditions in Sudan

- Much of Sudan’s geography is defined by the Nile river and its tributaries, winding through the country’s expansive plains. The Sahara desert sweeps across the north, rendering much of the land arid and unusable. However, in the Southern Savannah, especially the Southeast regions, summer storms deliver nearly 30 inches of rain each year. These fertile grasslands allow communities to fish, grow crops and raise livestock.

- Sudan has been plagued by one of the longest and deadliest civil wars in the world. For the past 27 years, President Omar al-Bashir has clung to power in a brutal fashion, including the 2003 genocide in Darfur that drew international condemnation. Fighting between the Sudanese government and southern rebels finally cooled in 2011 when an almost unanimous referendum granted what is now South Sudan independence. However, the violence within Sudan continues today. The constant war weighs heavy on the civilian population as more than 2 million people remain displaced in Darfur, with a PTSD prevalence of 55 percent in some areas.

- The 2011 secession of South Sudan sparked economic turmoil across the nation that continues to affect daily life. Prior to 2011, Sudan saw sustained economic growth from its vast oil reserves. The petroleum industry fueled nearly 95 percent of the country’s exports and was one of the largest areas of employment. Shrinking 2.3 percent in 2018, the economy has been in a downward spiral as 47 percent of the population lives below the poverty line and Sudan has the worlds second highest rate of inflation.

- The unemployment rate in Sudan have been slowly but consistently falling over the past two decades. In 1995, unemployment hovered around 14 percent. Today estimates place this rate at 12.5 percent. Conflict continues to afflict labor participation in some regions and the collapse of Sudan’s oil industry left thousands jobless. An unknown number of Sudanese are also engaged in non-wage work, primarily subsistence farming. Therefore, Sudan’s relatively low unemployment rate is not entirely indicative of the country’s economic standing.

- Agriculture is a driving economic force in Sudan, employing 80 percent of the labor force and comprising 40 percent of the country’s GDP. With two main branches of the Nile running through Sudan, the country boasts some of the most fertile lands in the region. In the White and Blue Nile plains, some farmers receive government subsidies to operate large scale, mechanized farms. These farms are integral to the economy, sometimes providing entire communities with steady work.

- Roughly 70 percent of the nation’s 39.5 million people live in rural areas where the government is unable to provide the most basic of services. Clean water, food and adequate sanitation are scarce in these regions and only 22 percent of rural residents have access to electricity. At 20 percent, rural unemployment in Sudan is almost twice as high as the national average, while the poverty rate jumps to 58 percent outside of urban areas.

- Some of the most notable improvements in Sudanese society have been in the education sector. In 2009, 67 percent of children attended primary school, increasing significantly from 45 percent in 2001. Although primary education is free, parent-teacher associations sometimes impose fees to cover the cost of school supplies. This can have a chilling effect on attendance. UNICEF estimates nearly 3 million children between the ages of 5 and 13 are kept out of school, one of the highest rates of out-of-school children in the entire continent.

- Hunger continues to impact communities across Sudan. In 2017, 3.8 million people suffered from food insecurity and in 2018, 5.5 million were affected. A staggering 80 percent of the entire population is unable to afford the food they need to sustain a healthy and nutritious diet and roughly 40 percent of Sudanese people are malnourished. Famine and conflict in neighboring South Sudan continue to bring refugees into the country, with only 1 percent of newcomers able to afford the food they need.

- Since 2000, the Sudanese government has doubled its annual health care budget, allocating 6.6 percent of its GDP towards health expenditures With only 5.6 doctors per 10,000 people, hospitals across the country are often overwhelmed. Despite much of the population residing in rural areas, most hospitals are located in Sudan’s urban centers and nearly two-thirds of the country’s doctors worked in the capital Khartoum. Malaria, yellow fever and diarrheal diseases are common throughout the country, especially in conflict-afflicted areas that lack public health initiatives and adequate medical supplies.

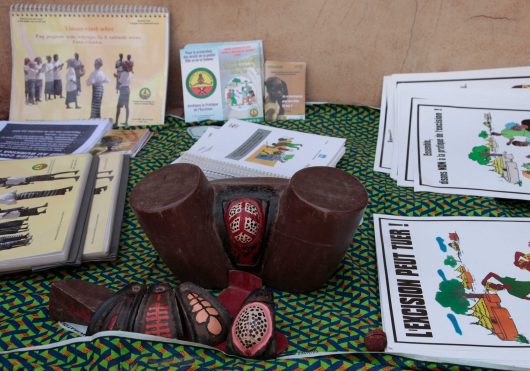

- Some reports suggest 87 percent of Sudanese women between the ages of 15 and 49 have been forced to undergo female genital mutilation (FGM), the highest rate in the world. However, with help from the World Health Organization, over 1,000 communities across the country have denounced FGM. The Sudanese government has also taken steps to address gender inequality, passing the 2008 Electoral Law that mandated 25 percent of parliamentary seats to be occupied by women. Today, women hold 30 percent of Sudanese Parliamentary seats.

These top 10 facts about living conditions in Sudan do not paint a hopeful picture for this African nation. But despite the various adversities imposed upon the people of Sudan, many are optimistic when it comes to the future. The historic protests dominating daily life since January indicates people are not afraid to mobilize for change. As pressure continues to mount on President al-Bashir, and his 27-year rule that dictated life for millions of oppressed people, could be coming to an end.

– Kyle Dunphey

Photo: Flickr

According to the

According to the

Unfortunately, in many countries around the world, women are not treated as equal to men. Ghana is not an exception, as women are more likely to live in

Unfortunately, in many countries around the world, women are not treated as equal to men. Ghana is not an exception, as women are more likely to live in  More than

More than  In 2017, five female Kenyan students

In 2017, five female Kenyan students  Five Kenyan teenage girls have been invited to participate in the finale of the international Technovation Challenge in Silicon Valley in August. They have developed I-Cut, an app fighting FGM, or female genital mutilation.

Five Kenyan teenage girls have been invited to participate in the finale of the international Technovation Challenge in Silicon Valley in August. They have developed I-Cut, an app fighting FGM, or female genital mutilation.