The International Social Service USA making a historic attempt to aid foreign countries in need is a perfect example of the benefits of foreign aid. The ISS has played a historic role in helping new immigrants, such as after World Wars I and II, when waves of immigrants struggled with adjusting to their new life in the USA after suffering shock and trauma. They also help with inter-country adoptions, helping children find safe and stable homes.

The organization’s international status allows all the national branches of the International Social Service to work together to optimally help the populations of countries with unsafe environments. After the 7.0 magnitude earthquake in Haiti in 2010, the U.S. branch stressed the importance of ceasing the adoptions during the critical time. Helping rebuild Haiti was the primary focus, and the ISS felt it was important not to interrupt or interfere with that process. They also felt that after suffering such trauma (both physical and mental), it would be better to let the children recover before they could be potentially adopted.

The ISS also is involved in helping to find missing family members or tracing birth families. The ISS-USA newsletter tells of Andrea von Barby Patterson’s search for her birth mother. Adopted at a young age from Germany by a family in Colorado, she was too late to meet her birth mother, who passed away, but was able to find other relatives including a half-sister, thanks to the organization.

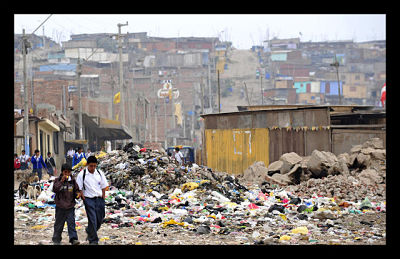

While the ISS doesn’t directly impact poverty, the organization certainly does help people in extreme poverty find homes in better conditions. Global poverty in different countries are similar in the big picture—children are considered a burden to parents who can barely take care of themselves. Basic necessities like water and food are unfulfilled, and having a child is an added burden. More often than not, the parents (and in some cases, it’s a single parent) are unable to take care of the child. This leads to high infant mortality and also high rates of child kidnapping and trafficking. In nations rampant with poverty, smuggling and kidnapping are other monsters to fear. Children are offered to be smuggled into other countries, or even kidnapped to be trafficked into other countries. In cases like these, the ISS also helps out a great deal by reuniting families. The ISS also helps childless couples in wealthier nations adopt these needy children.

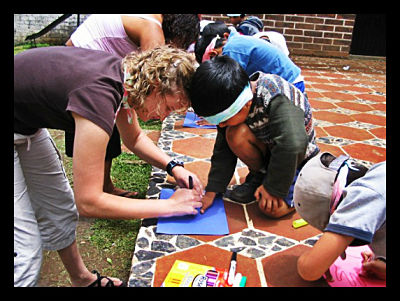

Since the 20th century, the USA branch of the International Social Services has been helping improve the conditions of children all over the world by helping them get adopted, helping them connect with birth families, and helping track down missing kidnapped or smuggled children. The much valued institute has contributed greatly to the global population with its charitable social work and continues to do so today.

– Aalekhya Malladi

Sources: International Social Service USA, ISS-USA Newsletter

Photo: International Programs