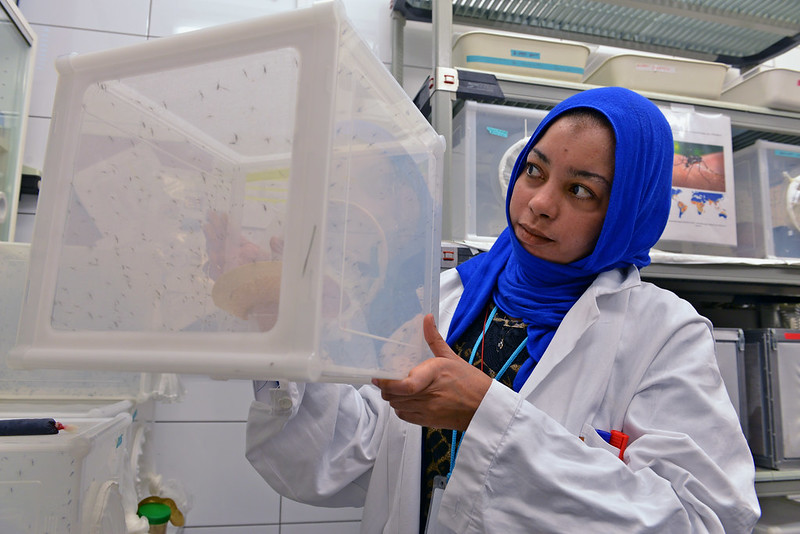

Vector-borne diseases comprise 17% of known infectious diseases, like malaria, Dengue fever and West Nile virus. Vector-borne diseases result from an infection transmitted to humans and other animals by vectors. Despite causing millions of cases each year worldwide, adverse climatic conditions can worsen the global burden of these infections and negatively impact human health.

Vector-borne diseases comprise 17% of known infectious diseases, like malaria, Dengue fever and West Nile virus. Vector-borne diseases result from an infection transmitted to humans and other animals by vectors. Despite causing millions of cases each year worldwide, adverse climatic conditions can worsen the global burden of these infections and negatively impact human health.

Effect of Adverse Weather on Vector-Borne Diseases

Vectors are sensitive to their environments. An increase in the earth’s average temperature presents a difficult challenge for addressing vector populations, as altered weather patterns and temperature changes affect vectors directly and indirectly. Rising temperatures can increase the speed of vector life cycles and breeding, which can increase vector populations and the speed of pathogen replication in hosts.

Indirectly, the weather changes impact the habitats and environments where these vectors exist and can change their geographic range and distribution. Mosquitoes, for example, breed in stagnant water; increased precipitation in some areas can amplify the number of vector breeding sites. These long-term changing weather patterns can increase vector’s geographic range, as warmer winter temperatures allow vector species to live in a larger area, increasing the range of the infections they spread to humans.

The burden of vector-borne diseases is highest in tropical and subtropical areas, disproportionately affecting the most impoverished populations. Malaria is one of the most prevalent vector-borne diseases globally, with an estimated 219 million cases and more than 400,000 deaths annually, according to the World Health Organization (WHO). Most of these deaths occur in children under five, with mosquitoes being the primary transmission vector.

Helpful Organizations

Many international organizations focus on this issue, working with the public health perspective and tackling changing climatic conditions to safeguard human health. GAVI, the Vaccine Alliance, has played a crucial role in combating vector-borne diseases by funding and supporting the distribution of vaccines for diseases such as yellow fever and Japanese encephalitis. GAVI-supported yellow fever campaigns in more than 10 African countries protected more than 130 million people. Its efforts have significantly increased vaccination coverage in low-income countries, reducing the incidence of these diseases and enhancing human health security.

While Gavi seeks immunization coverage for many diseases, the Malaria Elimination Initiative (MEI) focuses on eliminating malaria through surveillance and response, vector control, program management and drugs and diagnostics. MEI has a global focus and projects in South America, sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia. MEI has made significant progress in working at national, regional and international levels. Furthermore, the Nature Conservancy is an international organization with multiple priorities, including improving resilience for vulnerable habitats and communities, working with governments on clean energy policies and maximizing natural carbon storage opportunities through habitat conservation and agriculture practices.

Conclusion

The impact of changing temperatures on vector-borne infectious diseases is profound, exacerbating their global burden and highlighting the need for targeted investments and improvements. Investing in outbreak responses and enhancing disease surveillance systems is crucial to counter the increased infection potential from changing climatic conditions. These strategies can reduce exposure to vectors and susceptibility to vector-borne diseases, particularly in vulnerable populations. Additionally, investing in ecosystem stabilization and forest and wetland preservation can reduce greenhouse gas emissions, limit climate variability and contain vector habitats.

– Hodges Day

Hodges is based in San Francisco, CA, USA and focuses on Global Health for The Borgen Project.

Photo: Flickr

The consistent and widespread use of insecticides has significantly reduced the incidence of malaria by eliminating the disease’s vector, Anopheles mosquitoes. Unfortunately, this progress is threatened, as 60 countries have reported the existence of insecticide resistance in Anopheles mosquitoes. In 2012, the World Health Organization launched the Global Plan for Insecticide Resistance Management in Malaria Vectors to monitor this problem and try to generate solutions.

The consistent and widespread use of insecticides has significantly reduced the incidence of malaria by eliminating the disease’s vector, Anopheles mosquitoes. Unfortunately, this progress is threatened, as 60 countries have reported the existence of insecticide resistance in Anopheles mosquitoes. In 2012, the World Health Organization launched the Global Plan for Insecticide Resistance Management in Malaria Vectors to monitor this problem and try to generate solutions.