Global leaders often play a critical role in driving poverty reduction by casting decisive votes and implementing impactful policies. Indeed, around the world, several leaders have introduced programs that contribute to measurable poverty alleviation. Here are five global leaders who have focused on poverty reduction in their countries.

Global leaders often play a critical role in driving poverty reduction by casting decisive votes and implementing impactful policies. Indeed, around the world, several leaders have introduced programs that contribute to measurable poverty alleviation. Here are five global leaders who have focused on poverty reduction in their countries.

5 Global Leaders Driving Poverty Reduction

- Xi Jinping. Xi Jinping serves as the president of China, one of the world’s largest economies. Since he assumed office, the Chinese government reports that it has lifted 98.99 million people out of extreme poverty, defined as living on less than $1.69 per day. Poverty reduction has remained a central focus of national policy during Xi’s leadership.

The nearly 100 million people affected by this effort live in diverse regions. The government supported more than 128,000 villages in improving community development. - Katrín Jakobsdóttir. Katrín Jakobsdóttir is the Prime Minister of Iceland, one of the northernmost countries in the world. Jakobsdóttir is a well-respected feminist, known for her achievements in addressing poverty among women. In 2018, her administration enacted a law that prohibits unequal pay between men and women for the same work. In 2017, 13.6% of women in Iceland lived in poverty. Following the new law, that number dropped to 11.3% in 2018. By 2023, the poverty rate had fallen further to 8.9% for women and 9% for men.

- Narendra Modi. Narendra Modi is the Prime Minister of India, the most populous country in the world, located in South Asia. Since he took office in 2014, the Indian government reports that it has lifted 250 million people out of poverty. Over the last decade, India’s GDP per capita rose by $2,000, while 17% of the population moved above the poverty line. Modi’s administration continues to focus on sustainable development as part of its broader economic strategy.

- Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva. Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva is the President of Brazil, the largest country in Latin America. His success in reducing poverty is largely attributed to a social program he implemented called “Bolsa Família.” This program has reached more than 50 million people in Brazil, offering families in poverty financial benefits on the condition that they attend regular medical check-ups and ensure their children receive an education. This compromise has shown to be effective.

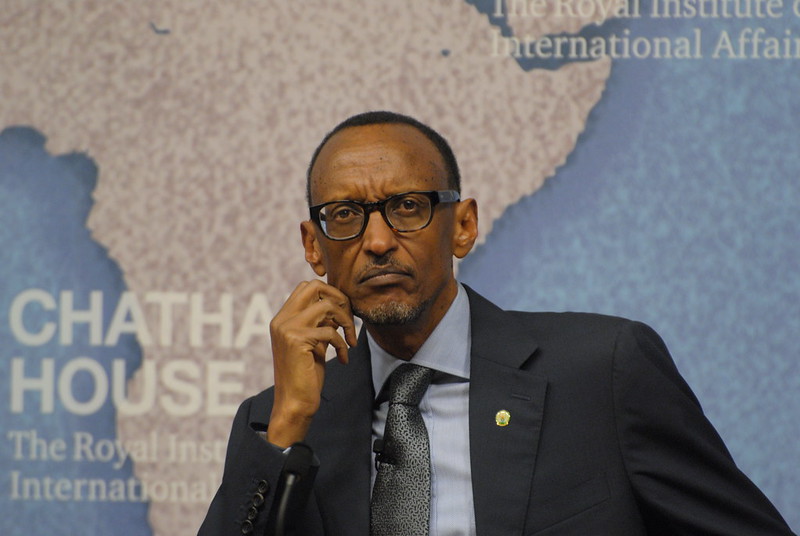

- Paul Kagame. Paul Kagame is the President of Rwanda, a country in central Africa near Lake Victoria. Upon taking office in 2000, Kagame launched a program called Rwanda Vision 2020, which has exceeded its initial expectations. In 2000, Rwanda’s poverty rate was 75.2%. However, by 2024, this figure had fallen to 38.2%. Rwanda has invested in agriculture, health care and education to improve livelihoods across the country. However, ongoing regional conflict involving the M23 militia poses challenges to further development.

Leadership and Poverty Reduction

These political figures demonstrate a range of approaches to poverty reduction, from equal pay laws to social protection programs. While each country faces unique challenges, the common thread among these leaders is their early and sustained commitment to addressing poverty through policy and investment. Their efforts offer useful models for other nations and underscore the importance of leadership in global poverty reduction.

– Nicholas East

Nicholas is based in Ashby, MA, USA and focuses on Politics for The Borgen Project.

Photo: Flickr

The United Kingdom’s (U.K.) foreign aid budget and international policies continue to shift, sparking concerns about their impact on global poverty alleviation. The government has committed to maintaining aid

The United Kingdom’s (U.K.) foreign aid budget and international policies continue to shift, sparking concerns about their impact on global poverty alleviation. The government has committed to maintaining aid

On the surface, China has been a powerhouse in diminishing global poverty. Measured by individuals living with less than $6.85 a day,

On the surface, China has been a powerhouse in diminishing global poverty. Measured by individuals living with less than $6.85 a day,  Technology increasingly offers more and more solutions to help reduce poverty across the globe. Considering South Sudan’s unpredictable climate and scarce resources, new technologies in South Sudan can provide a gateway of opportunities and security to the locals. This can be through new farming methods and equipment, schooling, banking and monetary management.

Technology increasingly offers more and more solutions to help reduce poverty across the globe. Considering South Sudan’s unpredictable climate and scarce resources, new technologies in South Sudan can provide a gateway of opportunities and security to the locals. This can be through new farming methods and equipment, schooling, banking and monetary management. Mumbai’s Dharavi is one of the world’s largest slums and is home to

Mumbai’s Dharavi is one of the world’s largest slums and is home to