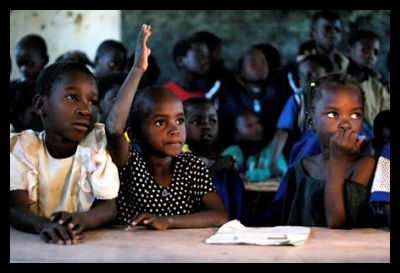

What if you did not have to go to school? For some school-aged children in America, this might be a dream, but for the children of the Solomon Islands, it is a nightmare—and a reality. Due to their high poverty rate, the Solomon Islands do not make education a requirement. Only 2.2 percent of the government’s budget goes toward education, dropping drastically from its 9.7 percent in 1998. Only 60 percent of children even have access to any kind of primary education.

What if you did not have to go to school? For some school-aged children in America, this might be a dream, but for the children of the Solomon Islands, it is a nightmare—and a reality. Due to their high poverty rate, the Solomon Islands do not make education a requirement. Only 2.2 percent of the government’s budget goes toward education, dropping drastically from its 9.7 percent in 1998. Only 60 percent of children even have access to any kind of primary education.

Of those 60 percent, only 72 percent of students complete their primary education. As for secondary school, the current numbers show 32 percent of boys attend, while 27 percent of girls do. Since there are so little resources, students have to take an exam to continue on to secondary school. Depending on their score, they can either be placed into secondary school or not score high enough to earn one of the few positions available.

These statistics all contribute to the 75 percent adult illiteracy rate. While education is not compulsory in the Solomon Islands, it is free for at least primary school. So, why are these numbers showing up?

The Solomon Islands had a civil war from 1998-2003, and once the country began to gain its footing again, a devastating tsunami hit in 2007. These events have only add to the hardships the people of the Solomon Islands face. Since adults have no educational background, the main source of income is through agriculture and farming. This can only get a family by for so long, and many children work alongside their families in lieu of going to school.

If a child does attend school, he or she has to deal with a shortage of teachers and classroom materials. Not only are half of all teachers unqualified, but they also struggle to receive payment for their services. In addition, less than half of the schools have access to adequate drinking water. Hopefully, the government will prioritize education in the coming years and break the cycle of poverty in the Solomon Islands.

– Melissa Binns

Sources: Classbase, Education in Crisis, ICDE

Photo: Flickr

In 2011, the Kazakhstani government requested technical assistance to improve the nation’s educational system. In response, the World Bank Group launched the Joint Economic Research Program, or JERP, in order to enhance the quality of education in

In 2011, the Kazakhstani government requested technical assistance to improve the nation’s educational system. In response, the World Bank Group launched the Joint Economic Research Program, or JERP, in order to enhance the quality of education in  There are quite a few economies around the globe that aren’t doing very well, but one country’s economy is beginning to emerge as a potential powerhouse: India.

There are quite a few economies around the globe that aren’t doing very well, but one country’s economy is beginning to emerge as a potential powerhouse: India.

Education in

Education in