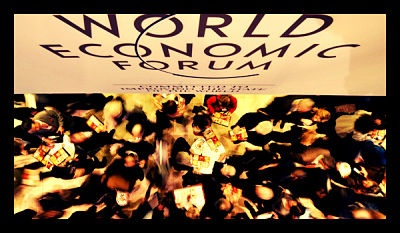

The World Economic Forum is colloquially coined as “Davos”, after Davos, Switzerland, the city in which the conference is housed annually. The WEF is an independent organization, dedicated to improving the economic state of the globe by incorporating leaders in business, politics, academics, and civil society to influence global, national, and industrial decisions.

Founded in 1971, the World Economic Forum started out as a humble group of business leaders, meeting under the umbrellas of the European Commission and the European Industrial Associations. The chair of the first gathering, Klaus Schwab, led 440 participants from over 30 countries in Davos to commemorate the finding of this non-profit organization, and created the building blocks to repeat the forum annually each January.

WEF is designed to be independent from any political, partisan, or national interest. This allows the participants in the forum to develop cross-cultural objectives to fighting economic weakness around the world.

A 1983 Forum document described the meetings as

“One of those increasingly rare international events where formality can be dispensed with, where personal contacts can be made, where new ideas can be tried out in complete freedom, where people are aware of the responsibilities involved in belonging to an international community, where we have time to look at the really important issues rather than everyday pressures. This is what we call the Spirit of Davos.”

The purpose of the WEF annual meetings varies from year to year, but all topics fall under the theme of ensuring that world leaders and attendees of the conference exercise their responsibilities “jointly, boldly, and strategically” to improve the economic state of the world for its future inhabitants.

WEF achieves this goal by collaborating with people, systems, and technologies to created indispensable leadership challenges to cultivate “new models, bold ideas, and personal courage to ensure that this century improves the human condition rather than capping its potential.”

In 1994, the World Economic Forum welcomed its 1,000th member, and decided to cap membership at that number, in order to ensure quality in member conversation and benefits.

– Kali Faulwetter

Source: Weforum, Weforum- Executive Summary

Photo: Business Week