Hunger in the Philippines is a rampant issue. Food insecurity affects 64.1% of total Filipino households. Further, an estimated 5.2 million Filipino families experienced involuntary hunger, hunger due to lack of food to eat, at least once in the past three months. One issue in particular is the increasing rate of youth hunger in the Philippines. Two in every 10 (19.1 %) Filipino children aged 0-59 months old are underweight. Additionally, three in every 10 (30.3%) of children the same age are stunted in growth. All of this is due to food insecurity. Due to these numbers, many organizations have stepped up to reduce youth hunger in the Philippines. Here are two organizations included in this fight against food insecurity in the Philippines.

Hunger in the Philippines is a rampant issue. Food insecurity affects 64.1% of total Filipino households. Further, an estimated 5.2 million Filipino families experienced involuntary hunger, hunger due to lack of food to eat, at least once in the past three months. One issue in particular is the increasing rate of youth hunger in the Philippines. Two in every 10 (19.1 %) Filipino children aged 0-59 months old are underweight. Additionally, three in every 10 (30.3%) of children the same age are stunted in growth. All of this is due to food insecurity. Due to these numbers, many organizations have stepped up to reduce youth hunger in the Philippines. Here are two organizations included in this fight against food insecurity in the Philippines.

Youth Hunger in the Philippines

One of the organizations making a tangible impact on youth hunger in the Philippines is Destiny Ministries International. One of its pastors, Ariel Tenorios, based in the City of Calamba, Laguna, has spearheaded a campaign to feed homeless youth on the streets. He also raises money to give aid packages to these malnourished children. His work has spread throughout the provinces to the General Santos City/Mindanao areas. Tenorios has helped children during the COVID-19 pandemic by provisioning meals to college-aged students and families struggling with food insecurity. To distribute these resources, his team goes from family to family in the poorer areas and gives out bags of food to those in need.

Another way in which Destiny Ministry International helps youth hunger in the Philippines is through social media. So far, the organization has been able to help hundreds of children and families struggling on the streets. One big issue during this time is mental health, with a lot of the youth on the streets struggling with anxiety and depression. Through its work, the organization has helped rehabilitate those in need. For example, it can help people work through suicidal thoughts by providing for their needs.

A Personal Touch

Norita Metcalf knows what is like to help out in these areas. Metcalf was born in the Philippines, living in the province of Cavite from birth to the age of 21. While she currently lives in the United States, she still works with various churches and organizations that focus on youth homelessness and food insecurity in the Philippines. Metcalf takes frequent trips back to the Philippines to help in both tangible and remote ways.

On her most recent trip to the Philippines, aiding Destiny Ministries International, she saw another level of poverty. She described cardboard houses, multiple stories high, that people made to give families some form of a roof above their heads, even if it is as thin as cardboard. This showed Metcalf a new level of poverty than what she personally experienced as a child in the Philippines. While there, she helped fundraise and pass out food to address this problem.

Destiny Ministries International

However, the work of Destiny Ministries International has helped make a tangible difference. Metcalf describes the ways in which people struggled not only with food insecurity but also mental health issues resulting from malnourishment and poverty. The provision of funds and food go a long way for these people. Many college-aged youths on the streets told Metcalf about the feeling of hopelessness associated with the lack of food. Even a small glimmer of hope resulted in the subsiding of suicidal thoughts and depression, thanks to the aid of Destiny Ministries International. Overall, its work has helped hundreds and reduced food insecurity for families struggling during the pandemic.

Children International

Another organization that has aided with youth hunger in the Philippines is Children International. This organization has sponsored over 43,000 kids and 14 community members for over 37 years. It helps tackle malnutrition through screening every child and identifying those who need intervention. Additionally, monitored supplemental feeding in community centers help these children regain their strength and correct their weight-height ratio. Children International also aids parents through nutrition classes that teach about healthy meals on limited budgets, so that children will not remain malnourished.

Through its community centers, such as the Kaligayahan Center (meaning “happiness” in Tagalog), the organization serves thousands of children in different areas. In this center alone, it provides medical and nutritional services to more than 5,100 children. The work that this organization does therefore helps to combat youth hunger in the Philippines. As a result, it helps stop the early deaths and malnutrition that Filipino youths often suffer through due to malnutrition.

Looking Forward

These two organizations demonstrate two different ways to fight impoverished conditions and youth hunger in the Philippines. The stark statistics on how many are affected show that stepping up to the challenge is a necessary step toward change. However, the fight is not done with just these two organizations. As demonstrated by Metcalf’s story, food insecurity is a serious issue that needs a coordinated response in the Philippines.

– Kiana Powers

Photo: Flickr

Traditional medicine, while not as popular or widely accepted as Western medicines, is a

Traditional medicine, while not as popular or widely accepted as Western medicines, is a  As COVID-19 started spreading, schools around the world shut down. For countries with already poor schooling systems and low literacy rates, the pandemic created even more challenges. The

As COVID-19 started spreading, schools around the world shut down. For countries with already poor schooling systems and low literacy rates, the pandemic created even more challenges. The  People often understand diseases as solely biological: an infectious pathogen harms the body and requires medical aid to defeat. However, disease also has social implications. Various social factors can impact not only someone’s likelihood of contracting a disease but also their likelihood of receiving quality medical care. One significant social implication affecting these factors is the stigmatization of disease.

People often understand diseases as solely biological: an infectious pathogen harms the body and requires medical aid to defeat. However, disease also has social implications. Various social factors can impact not only someone’s likelihood of contracting a disease but also their likelihood of receiving quality medical care. One significant social implication affecting these factors is the stigmatization of disease.

As of July 1, 2020, the World Bank reclassified the United Republic of Tanzania from a

As of July 1, 2020, the World Bank reclassified the United Republic of Tanzania from a  Nepal’s economy is heavily reliant on farming and livestock, with

Nepal’s economy is heavily reliant on farming and livestock, with

Joe Biden’s Vice President pick, Kamala Harris, is a new player when it comes to foreign aid and international relief. A strong arm with U.S./Mexico relations and domestic advocacy, Harris has some experience with addressing poverty. However, the question remains: what could this potential vice-presidential elect bring to the global table? This article will focus on Kamala Harris’ foreign policy. Specifically, her previous commitments to international humanitarian issues and what she outlines as her future focus.

Joe Biden’s Vice President pick, Kamala Harris, is a new player when it comes to foreign aid and international relief. A strong arm with U.S./Mexico relations and domestic advocacy, Harris has some experience with addressing poverty. However, the question remains: what could this potential vice-presidential elect bring to the global table? This article will focus on Kamala Harris’ foreign policy. Specifically, her previous commitments to international humanitarian issues and what she outlines as her future focus. Colleges quickly closed upon news of widespread COVID-19 infections in the U.S. Now, they must decide when to reopen.

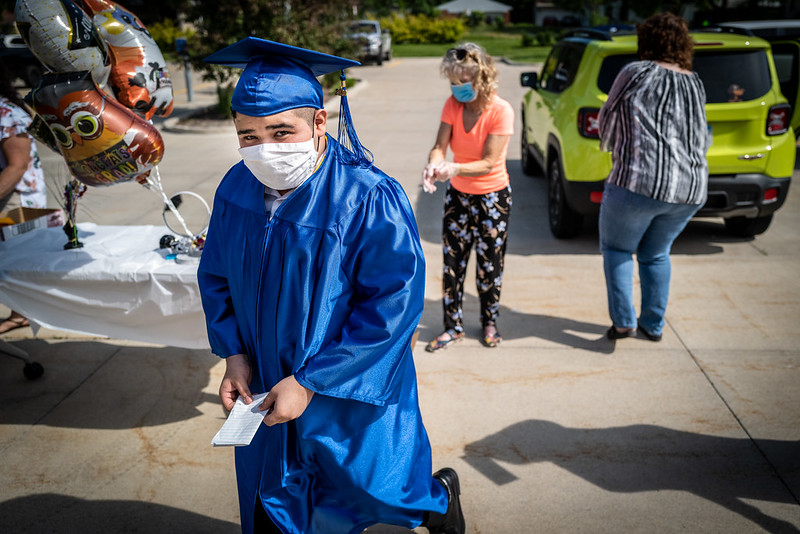

Colleges quickly closed upon news of widespread COVID-19 infections in the U.S. Now, they must decide when to reopen.