Third places are vital social spaces between work and home – offering individuals a sense of engagement, interaction and community. The popularity and availability of third places in Europe have faded with the rise of social media and the gentrification of inner-city neighborhoods. As one of the key frontiers providing local community touchpoints, third places support the well-being of individuals, especially those living or at risk of being near the poverty line.

Third places are vital social spaces between work and home – offering individuals a sense of engagement, interaction and community. The popularity and availability of third places in Europe have faded with the rise of social media and the gentrification of inner-city neighborhoods. As one of the key frontiers providing local community touchpoints, third places support the well-being of individuals, especially those living or at risk of being near the poverty line.

A Recent History of Third Places in Europe

Third places are social sites such as cafes, community centers and neighborhood environments, including local parks, sports grounds and places of worship. They have existed for centuries in human populations and the rise of the coffee house during the 17th Century is a popular example of third places in Europe. The COVID-19 pandemic saw the closure of local hang-out spots and widespread social distancing measures. The closures led to the permanent shutting of many local small businesses and a loss of community centers hit by significant funding cuts. As a result, critical spaces where people could engage in social interaction were lost.

Moreover, gentrification has only exacerbated a loss of inclusive third places in Europe. The process of gentrification in popular tourist and financial cities is transforming once-vibrant community areas into spaces of exclusion. For example, tourism-driven gentrification in Barcelona’s El Raval and Barceloneta neighborhoods led to increased rents, pushing out established local businesses or forcing them to adapt to tourist preferences. The accompanying social networks fostered in these spaces quickly dissolved.

Similarly, gentrification in Stockholm created “filter bubbles” and left low-income neighborhoods, often plagued by high levels of youth gang violence, without sufficient investment in social spaces for youth to develop away from the influence of gang activity and recruitment. While co-working spaces as “third places” in Mediterranean countries are on the rise, these are artificial spaces prioritizing productivity and professional networking rather than fostering meaningful, work-free social interactions. Co-working space identification as “third places” may be a more prominent symptom of a growing societal tendency to value individuals based on economic contribution rather than emotional well-being.

Social Media and the Cost of Third Places

The rise of virtual third places, especially social media, has contributed to the erosion of physical third places and the developmental process of learning social interaction. While social media platforms have created virtual connection spaces, they cannot replace the face-to-face interactions essential for community engagement and mental health. According to the Cigna Loneliness Index, Gen-Z, despite being the most digitally connected generation, reports the highest levels of loneliness.

Additionally, many third places are becoming increasingly expensive to frequent. For example, in London (U.K.), coffee prices have surpassed $6 in many establishments, making cafes and paid social spaces too expensive for regular visits in times of falling disposable incomes.

Mental and Physical Health Impacts

The role of third places in Europe is essential. The spaces are associated with improving quality of life, well-being and health. Third places provide crucial opportunities for social interaction. For instance, using third places (such as cafes) has been shown through multiple studies to improve how older adults can participate in society by providing informal support networks and social relationship-building to help combat cognitive decline and symptoms of depression later in life. The role of third places in combating loneliness is vital – with loneliness potentially cutting lives short by 15 years.

Third places in Europe also play a key role in helping mitigate poverty. Poverty is a multidimensional issue; however, social exclusion is both a determinant and by-product of some people’s realities of living in poverty. Without accessible third places, individuals living in poverty are more vulnerable to social exclusion, which further exacerbates their economic and mental health challenges.

Future Cities

For those living near the poverty line, access to these third places remains crucial for mental and physical health, as well as for preventing social exclusion. In the face of gentrification, digital spaces and rising costs, there is a pressing need for policies that prioritize creating and preserving accessible third places in Europe and its cities.

– Autumn Joseph

Autumn is based in London, UK and focuses on Business and Global Health for The Borgen Project.

Photo: Pixabay

In 2001,

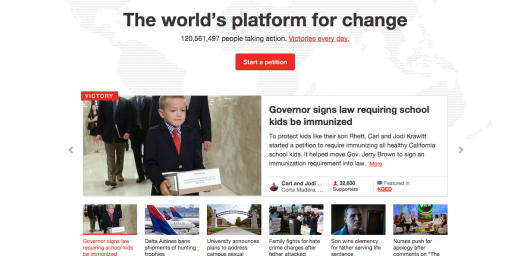

In 2001,  Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bill Gates all started their own movements to create social change. Without their influential work, the face of society would have a different set of rules. Truly, the world would be unrecognizable. During a time before the invention of the Internet, these influential thinkers had to convince society and the government that their way of thinking should be the norm.

Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr. and Bill Gates all started their own movements to create social change. Without their influential work, the face of society would have a different set of rules. Truly, the world would be unrecognizable. During a time before the invention of the Internet, these influential thinkers had to convince society and the government that their way of thinking should be the norm.