Health authorities declared a polio outbreak in Burundi after confirming three cases and finding the virus after wastewater surveillance in the country. After three decades of no documented cases, in the Isale district in western Burundi, a four-year-old boy and two children he was in contact with tested positive for poliovirus type 2. In places where poverty rates are high, polio tends to spread easily due to sanitary water scarcity and limited access to health care. Unfortunately, those with polio frequently find themselves in a vicious cycle of poverty with no social or financial support. With the most recent statistics showing Burundi having a poverty rate greater than 65%, the polio outbreak in Burundi presents major concerns.

Health authorities declared a polio outbreak in Burundi after confirming three cases and finding the virus after wastewater surveillance in the country. After three decades of no documented cases, in the Isale district in western Burundi, a four-year-old boy and two children he was in contact with tested positive for poliovirus type 2. In places where poverty rates are high, polio tends to spread easily due to sanitary water scarcity and limited access to health care. Unfortunately, those with polio frequently find themselves in a vicious cycle of poverty with no social or financial support. With the most recent statistics showing Burundi having a poverty rate greater than 65%, the polio outbreak in Burundi presents major concerns.

Public Health Emergency

The polio outbreak in Burundi constitutes a national health emergency, as poliovirus is extremely contagious. Since its first detection, health authorities have also confirmed five environmental samples of poliovirus type 2 in the wastewater.

Dr. Matshidiso Moeti, the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Regional Director for Africa, praises Burundi health authorities’ fast virus detection in a WHO press release. “The detection of the circulating poliovirus type 2 shows the effectiveness of the country’s disease surveillance. Polio is highly infectious and timely action is critical in protecting children through effective vaccination,” said Dr. Moeti.

How It Started

Poliovirus is transmitted through contaminated water and food. The virus lives in a person’s throat and intestines and spreads through fecal contamination. Early detection of cases is imperative to prevent the viral disease from spreading, as it is extremely contagious.

There are three types of wild poliovirus (WPV): types 1, 2 and 3. The symptoms of poliovirus often look similar to the flu and usually, last two to five days, though symptoms can be worse. Paralysis is associated with the most severe cases.

According to the Global Polio Eradication Initiative (GPEI), and echoed in the WHO’s press release, the cases detected from the polio outbreak in Burundi are “circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus type 2 (cVDPV2).”

The GPEI explains cVDPVs as variants of the poliovirus that can occur as a result of low vaccination rates among children. GPEI informs that areas with poor sanitation and low immunization rates can develop cVDPVs.

According to GPEI, the prevention of cVDPVs outbreaks is possible through immunization campaigns and the immunization of all eligible children. Previous efficient vaccination campaigns have alleviated the outbreak. The GPEI states “the vaccine continues to be a safe, effective tool for outbreak response across the continent.”

Addressing the Outbreak

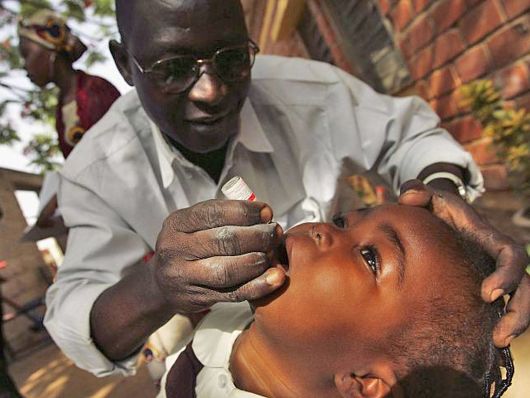

Since the Burundian government declared a state of public health emergency on March 17, they’re aiming to provide and administer vaccines to as many children under age seven as possible. The vaccine campaign is a necessary step in stopping the outbreak.

According to the CDC, the oral polio vaccine (OPV) and inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) prevent poliovirus infections. OPV contains a weakened version of one of the three types of poliovirus: IPV protects against all three poliovirus types, and contains no live virus.

Both the WHO and GPEI are assisting the Burundi health authorities in contact tracing and risk assessment to prevent a further outbreak in Burundi and nearby nations. Early detection of the virus is essential in containing the illness before it can spread. Burundi health authorities’ quick detection of the outbreak allowed the WHO and GPEI to begin contact tracing and rolling out vaccines efficiently. This efficiency since its first detection means that Burundi, the WHO and GPEI are in a great position to address the outbreak before it worsens.

Curbing the outbreak of polio before it spreads could save the lives of countless people in the country. And with the help of vaccines and other organizations intent on mitigating polio’s effects, those experiencing poverty in Burundi can look to the future with hope.

– Maya Steele

Photo: Flickr

Most think of polio as a disease of the past, eliminated from the world through scientific advancement. However, the disease remains present in some countries and runs the risk of spreading again if it is not contained. In the

Most think of polio as a disease of the past, eliminated from the world through scientific advancement. However, the disease remains present in some countries and runs the risk of spreading again if it is not contained. In the

Today, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO), in the largest public-private partnership in healthcare, has reduced

Today, the Global Polio Eradication Initiative in collaboration with the World Health Organization (WHO), in the largest public-private partnership in healthcare, has reduced