Sub-Saharan Africa is home to more than a billion people across countries with diverse cultures and economies. Yet across rural communities, a shared reality persists: poverty and limited health care access. Geographic isolation, underfunded health systems and economic hardship often make even basic care inaccessible, and the consequences are fatal. Under-5 child mortality in this region is 68 per 1,000 live births, while 70% of the global maternal deaths occur there. However, there are several grassroots health initiatives in place that aim to improve overall health care in these communities.

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to more than a billion people across countries with diverse cultures and economies. Yet across rural communities, a shared reality persists: poverty and limited health care access. Geographic isolation, underfunded health systems and economic hardship often make even basic care inaccessible, and the consequences are fatal. Under-5 child mortality in this region is 68 per 1,000 live births, while 70% of the global maternal deaths occur there. However, there are several grassroots health initiatives in place that aim to improve overall health care in these communities.

Background

Despite commitments like the 2001 Abuja Declaration, most countries in sub-Saharan Africa have not met health funding goals, hence, health systems remain vulnerable, dependent on fluctuating foreign aid. Consequently, even basic services involve out-of-pocket costs that deter those in poverty from accessing essential care.

Most rural areas lack nearby clinics and existing facilities often suffer from shortages in medicine, equipment and staff. As a result, many turn to traditional healers or informal providers. Chronic poverty, gender inequality and food insecurity further restrict access, especially for women who may lack the autonomy or resources to seek care.

Yet amid these challenges, hope is emerging from within. Across Ethiopia, Malawi and Nigeria, women and mothers are leading the charge through grassroots health initiatives ― bridging the gap between poverty and care by bringing services closer to those who need them most. Here are some grassroots health initiatives transforming rural sub-Saharan communities impacted by poverty and poor healthcare access:

Ethiopia’s Health Extension Program

Despite its low-income status, Ethiopia has made notable progress in rural health care through its Health Extension Program (HEP), launched in 2003. The program provides universal access to basic health services. It operates through local health posts staffed by trained Health Extension Workers (HEWs), many of whom are women from the communities they serve. HEWs identify pregnant women, provide antenatal care and refer them to formal health systems if complications arise.

More than 30,000 women received training and are now reaching more than 12 million households with health education, vaccination campaigns and family planning services. These, among other efforts contributed to Ethiopia meeting the under-5 mortality reduction target (MDG4) four years early in 2012, with major improvements in child and maternal health outcomes — including a reduction in infant mortality to only 68 per 1,000 live births.

Meseret’s Story: From Mother to Health Hero

Meseret, from rural Meki, grew up drinking polluted water from the nearby Lake Ziay. A visit from a community health worker introduced her village to water purification, inspiring her to train as a health worker. Today, she works with PSI’s Smart Start program, educating young couples on contraception and financial planning, empowering them to make informed decisions. Meseret’s efforts have contributed towards the 75,000 adolescent girls reached by Smart Start, more than 35,000 of which now use modern contraceptives — proof of the life-changing impact grassroots health workers can have on underserved communities.

The MaiMwana Project

In rural Malawi, where 73.9% of the population lives on less than $1.25 per day and maternal, neonatal and infant mortality rates are especially high, women-led initiatives like the MaiMwana project and Secret Mothers have become crucial.

Running from 2005 to 2010, the MaiMwana Project mobilized women in Mchinji District to identify health problems, create solutions, and implement interventions like home vegetable gardens and bicycle ambulances. Inspired by similar projects in Asia and South America, it formed 207 groups across 310 villages, involving more than 12,000 attendees, the majority of whom were women. The project contributed towards a 22% reduction in neonatal mortality, highlighting the life-saving potential of women-led, community-rooted health work

Secret Mothers

In Chiyang’anira Village, Chikwawa District, another grassroots solution has emerged: a group of women known as the Secret Mothers, or “Amayi Achinsinsi.” Previously, many pregnant women in the region avoided antenatal appointments due to the expensive 200 km journey to the nearest hospital, but Secret Mothers have improved this situation, supporting them by encouraging antenatal visits and modelling safe health practices. Since its inception in 2012, more than 100 women have joined, including 50-year-old mother Stella Sabstone, a founding member. Thanks to their efforts, eight in 10 expectant mothers now receive appropriate care. By building trust within familiar networks, Secret Mothers are transforming maternal health outcomes in the geographically isolated and economically disadvantaged community.

Grassroots Health Governance in Nigeria

In Nigeria’s Kaduna State, Ward Development Committees (WDCs) have emerged as a powerful community response to maternal health issues. Sparked by a maternal death in Yakasai village, the initiative, developed in collaboration with the Population and Reproductive Health Initiative, engages local leaders, health workers, and community representatives to improve health service delivery and accountability. WDCs promote health education, monitor local facilities and lead programs like the community Maternal and Perinatal Death Surveillance and Response (cMPDSR). These efforts have radically increased facility-based births and antenatal care use.

They also address cultural norms that hinder care. In some areas, WDCs have created policies encouraging the presence of male partners at antenatal visits, a critical shift in communities where health decisions are often male-dominated. While funding and sustainability challenges remain (such as the need for ongoing training), WDCs are helping to build a more responsive, locally-rooted health system to benefit the rural poor.

Grassroots Health Initiatives: Lasting Transformation

What unites these grassroots health initiatives ― from Ethiopia’s HEWs to Malawi’s women’s groups and Nigeria’s Ward Committees ― is their focus on empowering those most affected by poverty. By leveraging local knowledge, building trust, and expanding access, these programs are breaking barriers to health care in some of the world’s most underserved areas.

Women and mothers in particular are leading this transformation. Their leadership is not only radically improving health outcomes but also strengthening community resilience. These locally driven efforts demonstrate that scalable, cost-effective health solutions can emerge from within even the most resource-constrained settings, offering valuable lessons for broader poverty reduction strategies.

– Holly McArthur

Holly is based in Somerset, UK and focuses on Good News and Global Health for The Borgen Project.

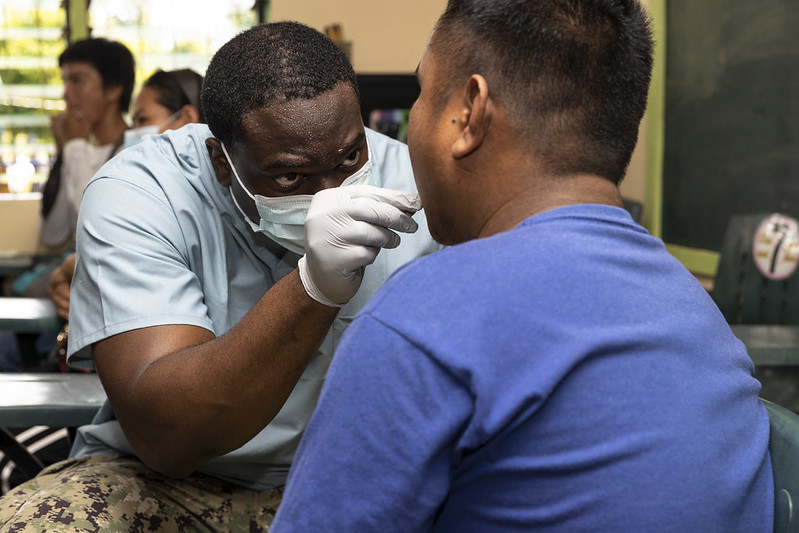

Photo: Flickr

Spain has emerged as a global leader in protecting infants from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), launching a successful immunization campaign that dramatically reduced hospitalizations and intensive care admissions. According to Salut, the campaign cut ICU admissions by 90% and hospitalizations by 87%, while the overall number of RSV infections dropped by 68.9%.

Spain has emerged as a global leader in protecting infants from respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), launching a successful immunization campaign that dramatically reduced hospitalizations and intensive care admissions. According to Salut, the campaign cut ICU admissions by 90% and hospitalizations by 87%, while the overall number of RSV infections dropped by 68.9%. Recently, India’s Tuberculosis (TB) control program has treated more

Recently, India’s Tuberculosis (TB) control program has treated more  Trachoma is an infectious disease causing in-turning of the eyelids, visual impairment and often irreversible blindness. The disease is associated with crowded households and inadequate hygiene, access to water, and access to and use of sanitation, primarily affecting women and children within

Trachoma is an infectious disease causing in-turning of the eyelids, visual impairment and often irreversible blindness. The disease is associated with crowded households and inadequate hygiene, access to water, and access to and use of sanitation, primarily affecting women and children within  Among the

Among the  Tyla Laura Seethal,

Tyla Laura Seethal,

Malaria remains a major global health concern, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO)

Malaria remains a major global health concern, especially in sub-Saharan Africa. In 2023, the World Health Organization (WHO)  From 1991 to 2002,

From 1991 to 2002,  Sub-Saharan Africa is home to

Sub-Saharan Africa is home to  In 2024, the

In 2024, the