What Is Malaria?

Malaria is a mosquito-borne disease that can spread to vertebrates. Symptoms can include fever and headaches as well as vomiting and, in extreme cases, death. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated 263 million malaria cases in 2023 alone.

In fact, travel is a major driver of malaria transmission in Southeast Asia. Understanding how migration influences the spread of the illness is essential to stopping it. Researchers and organizations in Bangladesh have developed several tracking methods, including travel surveys and mobile phone data.

Addressing the Issue

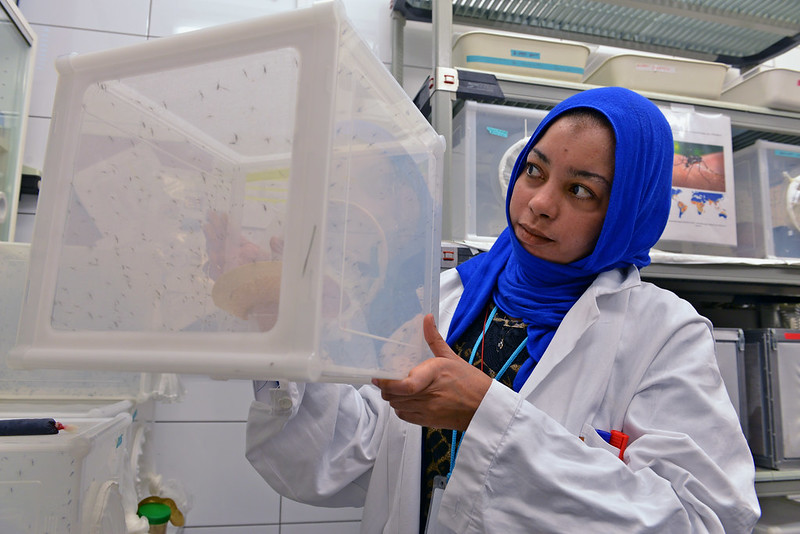

Climates like Bangladesh’s provide ideal breeding conditions for malaria-transmitting mosquitoes to thrive. This threat has been countered for decades with insecticide-treated nets; today, most families own at least one. However, these nets are insufficient to eliminate malaria; they primarily work to reduce transmission rates rather than fully eradicate the disease. To address malaria in Bangladesh, broader and more comprehensive solutions beyond nets are required.

Thankfully, nets are not the only tool Bangladesh has to combat malaria. In 2021, the WHO approved the first malaria vaccine, which Bangladesh quickly adopted and rolled out on as wide a scale as possible. Today, the country has established a strict treatment regimen for those afflicted, using the most up-to-date version of the vaccine to reduce the burden of the disease.

Additionally, in 2021, Bangladesh launched its National Strategic Plan for Malaria Elimination (2021–2025), outlining the ambitious goal of eliminating malaria from the country by 2030. The plan emphasizes early detection and treatment, monitoring evolving malaria strains, distributing insecticide-treated nets to at-risk populations and strengthening advocacy efforts to ensure widespread access to treatment.

Final Remarks

Malaria cases in Bangladesh have been steadily declining for years and the trend is expected to continue. From 2022 to 2023, infection rates fell by 9.2%, with predictions showing further decreases in the future. This consistent decline highlights Bangladesh’s perseverance, persistence and determination in combating the threat of malaria.

Bangladesh’s success proves that with the right mix of time, resources, international aid and strong leadership, no disease is unbeatable, not even one as deadly as malaria. The steady decline in cases shows what’s possible when governments, health organizations and communities work together toward a shared goal.

While challenges remain, Bangladesh’s progress stands as a powerful reminder that elimination is within reach and that with persistence, global health victories once thought impossible can, in fact, become reality.

– Cayle Harrison

Cayle is based in Columbia, SC, USA and focuses on Global Health and Politics for The Borgen Project.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons