David Kimani is a Kenyan man who grew up across the street from the largest landfill in the country. Being raised in the slums of Nairobi, Kimani dropped out after primary school.

David Kimani is a Kenyan man who grew up across the street from the largest landfill in the country. Being raised in the slums of Nairobi, Kimani dropped out after primary school.

Kimani, now a father of three, currently owns and operates a garbage recycling company, according to the Xinhua News Agency. He now earns about $30 a day selling recyclable trash in Nairobi. He has also hired five young people from similar backgrounds who face socioeconomic struggles.

Despite pressure from friends and family to pursue education, Kimani wanted to start a business. “I had done my own research and consulted widely with established players who convinced me that waste recycling promised returns. An older relative had earlier bought a car from the proceeds of garbage collection,” Kimani said.

According to UNICEF, approximately two-thirds of the population of Nairobi lives in informal settlements where they face issues of overcrowding, lack of health and educational resources, poor sanitation and social exclusion. According to ISID, only 12 percent of the households in the Nairobi slums have access to piped water.

Youth living in slums across Africa are less likely to attend school than children living in non-slum areas, according to the Institute for the Study of International Development (ISID).

The Nairobi county governor, Evans Kidero, honored Kimani’s young workers by agreeing to a government-funded contract that will help to clear trash in Nairobi out of residential areas.

He stated, “We will be spending 10,000 dollars every day for the next 45 days to ensure that Nairobi is restored to its former status as a green capital. Private contractors will partner with the National Youth Service to alleviate the garbage menace.” In addition, Kidero intends to form an incentives plan to encourage the youth to become full-time garbage collectors.

Caleb Kidali, a youth mentor for low-income children in Nairobi, noted the positive changes that employers can make to help youth from poor backgrounds afford to move out of the slums. “During its formative stages, garbage collection was like a hobby for bored youth until it evolved into a money minting exercise,” Kidali said.

Other companies, like Taka ni Pato (Trash is Cash), have started to hire young people to give them an employment and income opportunity and to enhance their communities by creating cleaner living spaces. In fact, Taka ni Pato has hired more than 100 young people to collect trash in Nairobi, benefiting the young people directly and the community as a whole.

– Kelsey Lay

Sources: Global Giving, Institute for the Study of International Development, UNICEF, Xinhua

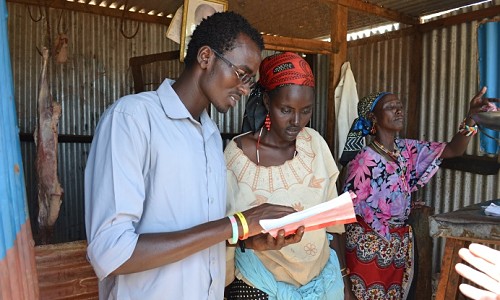

Photo: Google Images

When businesses promote the welfare of others by donating some of their profits or resources, they are participating in corporate philanthropy. This philanthropy can be in the form of financial contributions, use of facilities, services, time or advertising support. Corporations often also set up employee volunteer groups and create matching programs. Some companies manage their own philanthropy, while others organize theirs through company foundations.

When businesses promote the welfare of others by donating some of their profits or resources, they are participating in corporate philanthropy. This philanthropy can be in the form of financial contributions, use of facilities, services, time or advertising support. Corporations often also set up employee volunteer groups and create matching programs. Some companies manage their own philanthropy, while others organize theirs through company foundations.