With the current Ebola outbreak, it is no wonder people are in a rush to help fight the treacherous disease. Although no known cure has been found, there are preventive measures one can take to halt its transmission.

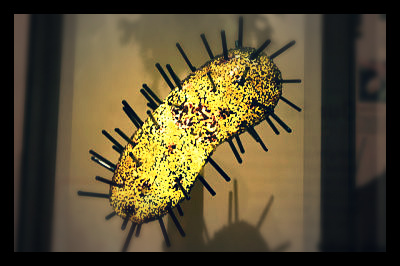

Ebola is often transferred to humans from wild animals and can spread in the population through human-to-human contact with bodily fluids. Fruit bats are common vectors that transfer Ebola to humans through contact with blood, sweat and secretions.

Further, health workers are at great risk of contracting the disease when they treat patients with Ebola without proper protective gear. The average case fatality rate is at about 50 percent, but past outbreaks have had an average fatality rate of 90 percent. In 1976, the first outbreaks of the disease were recorded in the outskirts of Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo. Ebola has since moved on to urban and rural areas of West Africa, as we are witnessing currently.

But how can we help fight Ebola? The World Health Organization claims that community participation is key in controlling outbreaks. There needs to be clear interventions set in case of rapid progression throughout the country, such as case management and surveillance, an adequate laboratory and effective burial methods.

Health care providers that are in close contact with the virus should wear gloves, masks and goggles, in turn diminishing chances of infection. In addition, people should stay clear of highly infected areas or restrict travel to countries with high prevalence of Ebola.

Since symptoms can take up to three weeks to manifest, it is crucial that people are aware of the risk factors for infection. Interaction with wildlife increases one’s chance of infection, and so to help fight Ebola, limit contact and always wear gloves and masks if working with animals. Also, if living in high-risk areas in Africa, make sure meat is cooked properly and thoroughly before consumption. Furthermore, when coming in contact with patients with Ebola, wash hands regularly. This includes contact with the living and the deceased. Thus proper and safe burial is essential for affected persons.

As the recent cases of health care workers in Dallas demonstrate, strict infection control measures and following protocols from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention must be followed to help fight Ebola. Community engagement and education is also key in successfully controlling the outbreak. While an approved vaccine does not yet exist, the virus can be contained through protective measures that can effectively reduce human transmission.

– Leeda Jewayni