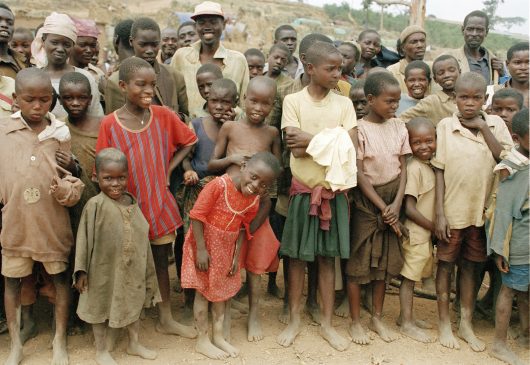

The Borgen Project sat down with Brian Endless, a political science professor at Loyola University Chicago and an academic expert on the Rwandan genocide. Since 2007, Endless worked closely with Paul Rusesabagina, the inspiration for the film “Hotel Rwanda,” to raise awareness about misconceptions surrounding the 1994 Rwandan genocide.

How and why did you initially become interested in the Rwandan genocide?

“[My interest] started around the time I started grad school. I had always focused on the Security Council, and I had a lot of experience with it. I was immersed in the genocide from the beginning from an international perspective. I knew what was happening and saw it as a huge failure of the U.N. I saw everything from the perspective of the outside world.

I didn’t really know how little I knew about Rwanda until 2007 when I met Paul Rusesabagina, who had become an international spokesperson for Rwanda. I had no idea about the history of the civil war and internal conflicts that led up to the genocide. From 2007 on, I went on a pretty steep learning curve, picking up everything that I could about what was happening inside of Rwanda.”

Can you summarize your experience learning about and advocating for awareness of the genocide after 2007?

“From extensive talks with Paul and members of the Rwandan expatriate community, I learned that while the international public saw the situation as Hutus killing Tutsis, what was actually happening was the latest in a series of civil wars. I was surprised by the fact that an enormous number of Hutus died during the genocide, and that a Tutsi dictatorship had replaced a Hutu dictatorship, and that a small percentage of Tutsis was ruling and committing substantial human rights violations.

I did an enormous amount of academic reading and I followed a lot of court cases as things came into the public press. I started actively working with Paul and writing speeches for him and things to be published and publicly disseminated. The Hotel Rwanda Paul Rusesabagina Foundation was first campaigning to inform the public that there were still problems. The situation was really just, ‘meet the new boss, same as the old boss’ with a population that was being discriminated against. Rwanda was also a very friendly government to the United States, so it was difficult getting information out and advocating for truth and reconciliation in Rwanda.”

What were the biggest driving factors behind the genocide?

“It’s a story that dates back to pre-colonial times. By 1990, a Hutu government was in charge but didn’t have enormous control over the country. Tutsi groups in Uganda started a civil war to take back the country. Tutsis were largely winning the war in 1993, and there was a peace plan. By early 1994, the peace plan was breaking down. Hutu extremists started to bring out negative views against the Tutsis. In part, it was a plan to try to stop the Tutsi invasion by encouraging Hutus to demonize Tutsis. They focused especially on internally-displaced youth who were pushed out of their homes as the Tutsis invaded.

That’s effectively where the genocide started. The genocide officially started when the plane carrying the president of Rwanda and the president of Burundi was shot down in early April 1994. That triggered the genocide, and Hutu Power radio began to say, ‘It’s time to chop down the tall weeds,’ which was code to kill the Tutsis.”

How did the international community fail to become involved in the Rwandan genocide?

“We had just come out of Somalia, where 18 U.S. army rangers had been killed. The Clinton Administration used this as an excuse to pull us out. What happened was the U.S. public became more against using forces in places they didn’t understand or that weren’t strategic. Rwanda was a place where nobody had close ties. There were really no great natural resources, thus we let it happen and let it go on. People in the U.S. and in Europe didn’t realize it until we saw it on CNN, and our politicians had no interest in getting us involved in another war that could end up like Somalia.”

What do you think should have been done?

“Really the question is: If we’re going to say ‘never again’ after a genocide, we have to decide if we mean it or not. So far, we haven’t meant it. We’re not willing to put resources on the ground even when we know what’s happening, and in the case of Rwanda, we absolutely knew that genocide was happening.”

What do you think can be done to prevent future genocides around the globe?

“I think in the future, a piece of it is: how can we make the American people more interested and more knowledgeable about what happens in other parts of the world? If the press chose to highlight these things, they would become more important. Advocacy groups need to convince both press and politicians that these are issues of interest to Americans. People need to understand that we have some culpability because we have our fingers pretty much every place in the world. People too often think, ‘Oh, that’s not our problem,’ or, ‘Oh, they should solve their own problems.’ A big piece of our own problem is that we don’t look at things from a humanitarian perspective.”

Endless continues to advocate for the elimination of genocide by working with Paul Rusesabagina’s foundation and teaching classes at Loyola University Chicago. Endless’ insights into the Rwandan genocide offer a path to an international community that can genuinely say “never again” to genocide.

– Peyton Jacobsen

Photo: Flickr

New job-training programs in Rwanda are helping unemployed youth gain practical skills that allow them to find meaningful work. The Educational Development Center (

New job-training programs in Rwanda are helping unemployed youth gain practical skills that allow them to find meaningful work. The Educational Development Center (

It is the time of year to reflect on achievements and the need for change. The World Economic Forum 2016 Report on the Global Gender Gap points to both.

It is the time of year to reflect on achievements and the need for change. The World Economic Forum 2016 Report on the Global Gender Gap points to both.