Colombia’s healthcare system is not perfect but it also far from inadequate. Located in the northernmost part of South America, Colombia has estimable healthcare provision for the country’s people. With both public and private insurance plans, reputable facilities and well-equipped healthcare providers, Colombia sets an example of what sufficient healthcare looks like in a developing country. To understand this better, it is necessary to know some key facts about healthcare in Colombia.

Colombia’s healthcare system is not perfect but it also far from inadequate. Located in the northernmost part of South America, Colombia has estimable healthcare provision for the country’s people. With both public and private insurance plans, reputable facilities and well-equipped healthcare providers, Colombia sets an example of what sufficient healthcare looks like in a developing country. To understand this better, it is necessary to know some key facts about healthcare in Colombia.

7 Facts About Healthcare in Colombia

- Healthcare in Colombia ranked 22nd out of 191 healthcare systems in overall efficiency, according to the World Health Organization. For perspective, the United States, Australia, Canada and Germany ranked 37th, 32nd, 30th and 25th respectively.

- Colombia’s healthcare system covers more than 95% of its population.

- Indigenous people are considered a high-risk population due to insufficient access to healthcare in indigenous communities in Colombia. Specifically, they are more vulnerable to COVID-19 due to this lack of healthcare access and significant tourist activities in indigenous regions increase the risk of spread. Robinson López, Colombian leader and coordinator for Coordinadora de las Organizaciones Indígenas de la Cuenca Amazónica (COICA), said in March 2020 that tourism in indigenous territories in Latin America should stop immediately to curb the spread of COVID-19.

- There are inequities in the utilization of reproductive healthcare by ethnic women in Colombia, according to a study. Self-identified indigenous women and African-descendant women in the study had considerably less likelihood of having an adequate amount of prenatal and postpartum care.

- The Juanfe Foundation is a Colombian-based organization that promotes the physical, emotional and mental health of vulnerable and impoverished adolescent mothers and their children. So far, the organization has supported more than 250,000 people. The Juan Felipe Medical Center served 204,063 individuals — 20% of the population in Cartagena, Colombia. The organization also saved the lives of 4,449 infants through its Crib Sponsoring Program.

- In 2019, four of the top 10 hospitals in Latin America were in Colombia and 23 of the top 55, according to América Economía.

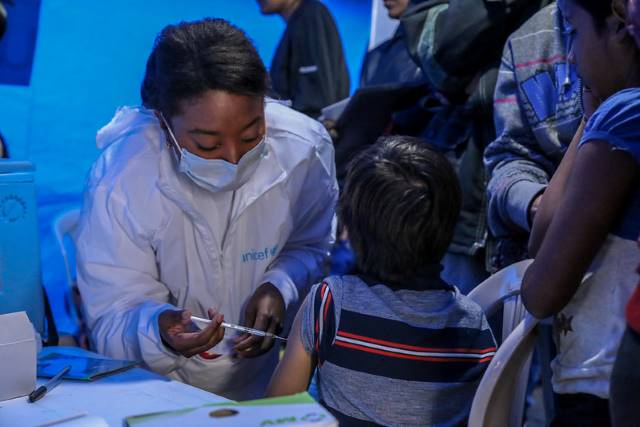

- Colombia secured nine million doses of the COVID-19 vaccine from Johnson & Johnson in December 2020. Combined with the doses it will receive from Pfizer, AstraZeneca Plc, COVAX and other finalizing deals, Colombia will be able to vaccinate 35 million people within its population of 49.65 million, striding toward herd immunity.

Recognizing Colombia’s Healthcare System

Simultaneously recognizing the current inequities and challenges alongside the positives in Colombia’s healthcare system is the true key to understanding it and the individuals depending on it overall. Despite attention-worthy deficits, healthcare in Colombia stands out in Latin America and in the world as high quality, widespread and respectable. The country’s healthcare is contributing to the well-being of many and the future ahead looks promising.

– Claire Kirchner

Photo: Flickr

Year after year, Japan consistently ranks as one of the top countries for life expectancy. These top 10 facts about life expectancy in Japan is a reflection of economic developments that occurred since World War II.

Year after year, Japan consistently ranks as one of the top countries for life expectancy. These top 10 facts about life expectancy in Japan is a reflection of economic developments that occurred since World War II. With nearly 40,000 people, Monaco is one of five European micro-states and is located on the northern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Monaco has one of the

With nearly 40,000 people, Monaco is one of five European micro-states and is located on the northern coast of the Mediterranean Sea. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Monaco has one of the Austria is known for having one of the most generous and greatest healthcare systems across the world. Healthcare needs are readily accessible to Austrian citizens at little to no cost. The vast majority of the Austrian population has access to healthcare, as long as an individual is not willingly choosing to be unemployed.

Austria is known for having one of the most generous and greatest healthcare systems across the world. Healthcare needs are readily accessible to Austrian citizens at little to no cost. The vast majority of the Austrian population has access to healthcare, as long as an individual is not willingly choosing to be unemployed.

According to the European Consumer Health Care Index of 2019, the Czech Republic’s healthcare system is

According to the European Consumer Health Care Index of 2019, the Czech Republic’s healthcare system is