Not only are these workers often paid unfair wages, but they also often suffer from extremely unsafe working conditions. In 2013, for instance, the collapse of a poorly-built factory in Bangladesh killed over 1,000 people, according to The Guardian.

Garment Industry in Bangladesh

Bangladesh, like many other developing countries, is highly dependent on the garment industry. This means that companies who fail to treat workers respectfully can defend themselves against critics by claiming they provide jobs to people who would not otherwise be able to work.

There is some sense to such a claim. According to The Guardian, 80 percent of Bangladesh’s GDP relies on the ready-made garment industry.

Nevertheless, it is certainly possible for garment companies to do more, both to protect workers as well as to support support development of the economies and societies in which those workers live.

People Tree: A Company Making Changes

One company that has proven to be true is People Tree, a London and Tokyo-based brand that aims to be 100 percent Fair Trade throughout its supply chain.

People Tree has attracted the attention of The Guardian, The Telegraph and other prominent publications for its commitment to Fair Trade policy.

In 2013, it became the first clothing company in the world to receive the product mark of the World Fair Trade Organization.

On its website, People Tree states that “people and the planet are central to everything we do.”

Central to its business model is what the People Tree calls “Slow Fashion,” which is a philosophy that rebels against the high-speed mode of trade that is standard in the fashion industry. It is that rushed mentality that leads to socially and environmentally hazardous practices.

As People Tree’s website defines it, “Slow Fashion means standing up against exploitation, family separation, slum cities and pollution—all the things that make fast fashion so successful.”

With regard to the environment, People Tree engages in a number of sustainable practices ranging from the use of certified organic cotton to dyeing with safe and azo-free chemicals. Products are sourced locally and from recycled material when possible. Once the products are made, People Tree prioritizes shipping by sea over shipping by air, thereby reducing the company’s impact on global warming.

Perhaps most importantly, People Tree’s fabric is woven by hand. Specifically, by the hands of real people whom the company strives to pay well and treat with dignity.

Indeed, one of the reasons People Tree cares so much about environmental friendliness is that it understands the effect pollution has on the environments in which their workers live. Environmentally conscious practices lead to sustainable development and happier workers, which in turn lead to higher productivity and more business, according to the company.

People Tree makes 50 percent advance payments on orders so that farmers and producers can more easily finance Fair Trade. And it manages its Collections so that workers will have enough time to produce garments by hand without being crunched, which the company says “is rare in the fashion industry.”

Setting the Stage for Sustainable Fashion

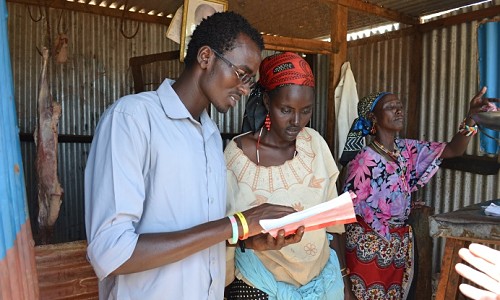

People Tree goes beyond paying fair wages and maintaining safe conditions, however. In some communities, it provides clean water and offers free education to poor families. In many cases, People Tree partners with organizations that empower disadvantaged workers, such as women and the physically disabled.

A new precedent has been established for the garment industry, as social business and corporate responsibility become increasingly popular in other industries. People Tree’s success demonstrates the potential for companies to think beyond profit and consider the wider impact business can have on impoverished communities in developing countries.

– Joe D’Amore

Sources: Telegraph 1, Telegraph 2, People Tree, The Guardian 1, The Guardian 2

Photo: Flickr