The recruitment and use of child soldiers in Mali has remained a persistent and often overlooked outcome of the country’s deepening instability. Since armed conflict first erupted in 2012, children have been drawn into roles far beyond their years – fighting on frontlines, acting as scouts and serving logistical roles under coercive or deceptive conditions. Despite clear international prohibitions, armed groups continue to involve minors in a war that disregards age or consent.

The recruitment and use of child soldiers in Mali has remained a persistent and often overlooked outcome of the country’s deepening instability. Since armed conflict first erupted in 2012, children have been drawn into roles far beyond their years – fighting on frontlines, acting as scouts and serving logistical roles under coercive or deceptive conditions. Despite clear international prohibitions, armed groups continue to involve minors in a war that disregards age or consent.

Conflict and the Machinery of Recruitment

The security crisis in Mali began more than a decade ago, first triggered by a coup and fueled by the rise of jihadist groups. In areas where the state has lost its grip, nonstate actors have filled the vacuum. Among them, Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) – an al-Qaeda affiliate –has become one of the most active recruiters of children. In 2022, the United Nations (U.N.) verified 394 cases of child recruitment in Mali. The real figure, aid workers suggest, is likely much higher. Children are also recruited by local defense groups and pro-government militias, particularly in regions like Mopti and Gao. While some join voluntarily due to desperation, others are forcibly conscripted or manipulated through promises of safety or income.

Why Children Are Vulnerable

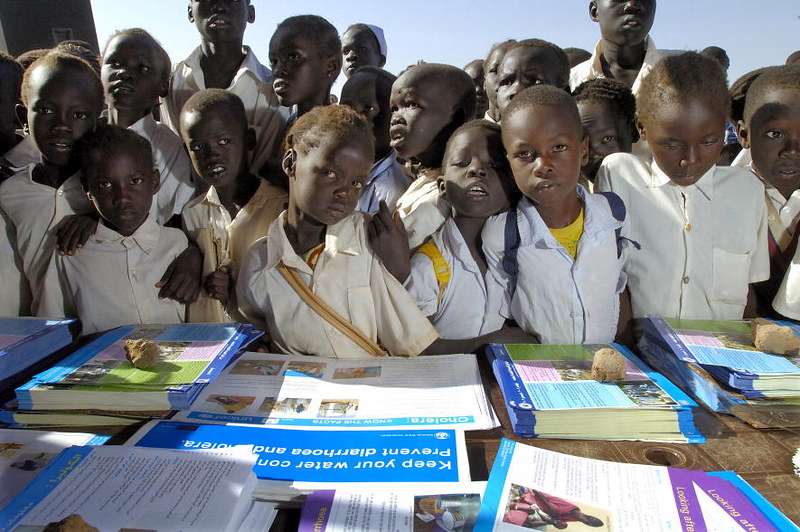

In rural Mali, children often face an impossible choice: survive or surrender. Many lack access to basic education, food or protection. With livelihoods disappearing and schools destroyed, some see joining armed groups as the only path forward. In many cases, entire families rely on armed factions for security and children volunteer out of obligation or necessity. Girls are especially at risk. Armed groups frequently subject them to sexual violence, domestic labor and forced marriages. These experiences often go unreported but leave deep and lasting trauma.

Legal Promises and Local Realities

International law, including the Optional Protocol to the Convention on the Rights of the Child, clearly prohibits the use of children under 18 in hostilities. Mali signed an action plan with the U.N. in 2017 to end the recruitment of children by state forces. However, enforcement has been weak. While the Malian government no longer officially recruits children, armed groups continue to do so with little consequence. Security forces lack control in large parts of the country, allowing nonstate actors to operate freely. As a result, the use of child soldiers in Mali has persisted in both open combat and support roles.

Reintegration and Recovery

Children who leave armed groups often return to communities that may no longer exist or that regard them with suspicion. Without structured reintegration, many remain vulnerable to poverty, re-recruitment and long-term psychological trauma.

In 2023, the Mali Humanitarian Situation Report documented that 42 children formerly associated with armed forces and groups received protection and reintegration support in the Mopti and Ségou regions. This assistance included case management, family reunification and access to essential services such as psychosocial care and education.

UNICEF, in partnership with local and international actors, continues to support such initiatives. These ongoing efforts often involve the establishment of safe spaces, vocational training, trauma counseling and education catch-up programs. However, the scope of support remains limited compared to the scale of need. Globally, the organization emphasizes a comprehensive reintegration approach that includes community-based services, psychosocial support and family tracing. In Mali, this approach is critical to reducing the likelihood of re-recruitment and helping former child soldiers rebuild their lives.

A Global Call for Action

The child soldier crisis in Mali continues to pose significant challenges to national and regional stability. The porous borders of the Sahel region have facilitated the spread of conflict into neighboring countries such as Burkina Faso and Niger, exacerbating humanitarian concerns. According to UNICEF, 10 million children across these three nations are in urgent need of humanitarian assistance, with nearly 4 million at risk in adjacent countries due to escalating hostilities. This situation underscores the critical need for sustained international support to address the root causes of child recruitment and to provide comprehensive reintegration programs.

Looking Ahead

Ongoing insecurity in Mali presents significant challenges for child protection. As armed groups continue to operate across vast ungoverned territories, efforts to prevent child recruitment remain limited in reach and resources. Reintegration programs supported by humanitarian partners have demonstrated effective strategies. Sustainable solutions potentially require increased coordination, long-term investment and integration of services across sectors, including education, mental health and family support. Strengthening national frameworks and expanding community-based interventions may help reduce future recruitment and support recovery for affected children.

– Charlie Baker

Charlie is based in London, UK and focuses on Politics for The Borgen Project.

Photo: Flickr

For

For

Pakistan is an emerging middle power within the East Asia hemisphere quickly on the incline to becoming one of the world’s largest militaries and economic power in the East. However, for all its recent growth, a multitude of issues still plague the nation; terrorism, corruption, religious strife, illiteracy and

Pakistan is an emerging middle power within the East Asia hemisphere quickly on the incline to becoming one of the world’s largest militaries and economic power in the East. However, for all its recent growth, a multitude of issues still plague the nation; terrorism, corruption, religious strife, illiteracy and

Ethiopia’s long history of armed conflicts endangers the well-being of children, subjecting them to trauma and putting them at risk of recruitment for combat.

Ethiopia’s long history of armed conflicts endangers the well-being of children, subjecting them to trauma and putting them at risk of recruitment for combat.