With more than half of the Rohingya refugees being children, the issue of education becomes an important matter, especially for girls. The widespread cultural and religious norms that prioritize domestic responsibilities for girls over education and the perception that sharing classrooms with boys is inappropriate, contribute to many girls dropping out as they grow older. The Rohingya Refugee Response reports that 24% of teenage girls are not in school due to family restrictions, while 12% are not in school due to early marriages.

With more than half of the Rohingya refugees being children, the issue of education becomes an important matter, especially for girls. The widespread cultural and religious norms that prioritize domestic responsibilities for girls over education and the perception that sharing classrooms with boys is inappropriate, contribute to many girls dropping out as they grow older. The Rohingya Refugee Response reports that 24% of teenage girls are not in school due to family restrictions, while 12% are not in school due to early marriages.

UNICEF’s Education Initiative

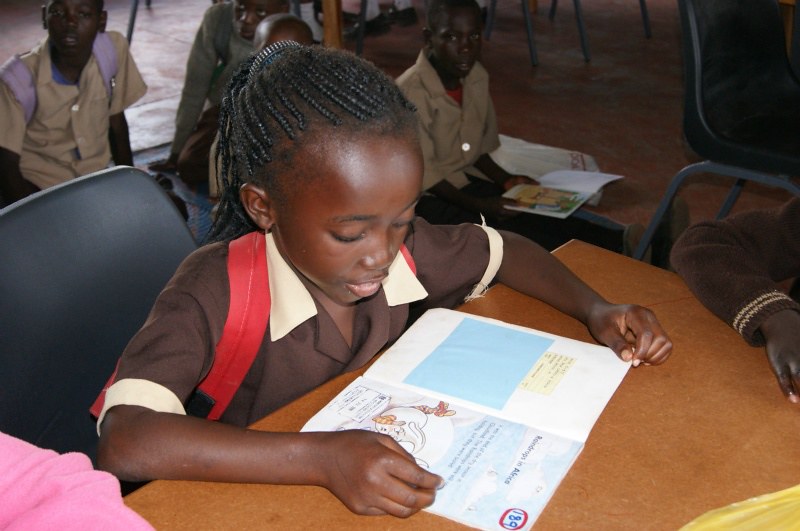

To address these challenges, UNICEF’s education initiative, in collaboration with 45 partner organizations, has played a successful role in expanding education for Rohingya girls. With support from NGOs such as the Global Partnership for Education, which contributed $11 million just in 2023, the initiative established more than 3,500 learning centres. Today, 80% of children aged 6-11 are part of learning centres with a high attendance rate of 83% and a similar proportion between boys and girls.

Still, enrollment rates decline as girls grow older. As a response, UNICEF began implementing girls-only classrooms in 2022 and increased the number of female volunteers from 71 to 305. These changes were made in recognition of cultural sensitivities, where many families believe girls should not study alongside boys or the fear that girls may be harassed outside the home. As a result, more female teachers, volunteers, and girls-only classrooms helped reassure and encourage parents to keep their daughters in school, increasing the number of girls in secondary education from 17% to 24% over the past two years.

Despite progress, the initiative has recently been facing challenges due to a funding crisis. Some learning centres had to close while others struggled with limited learning materials and a lack of qualified teachers, especially at the secondary level. The 50,000 estimated new arrivals in the camp and another 50,000 refugees waiting for registration further exacerbate this issue, according to the Rohingya Refugee Response.

The 2025-26 Joint Response Plan

To mitigate such challenges, the 2025-26 Joint Response plan, launched on March 24, calls for $71.5 million. Part of this will come from the 2025 Complementary Development Fund to maintain and establish learning facilities.

Another key component of the plan is its aim for a more inclusive education for children aged 3-18. This includes the launch of Early Childhood Development, Accelerated Learning Programmes for over-aged learners, and flexible learning arrangements for disabled children. It also reiterates efforts to continue to encourage girls’ enrollment and attendance by establishing more female-only classes and increasing the recruitment of female teachers.

Notably, the plan states that the education will continue to follow the Myanmar curriculum delivered in Burmese, the Myanmar language. This not only helps preserve cultural identity but also prepares children for eventual repatriation to Myanmar in the future.

The Future

Education for Rohingya girls is a right, a shield against child marriage and labour, and a step toward financial stability. Thanks to the help of volunteers, UNICEF’s education initiative and the support from its partner, thousands of Rohingya girls have gained access to education which opened doors to bigger opportunities. However, as funding falls short, international support is essential more than ever. Only through continued investment can we ensure that these girls will have the chance to learn, grow, and lead.

– Lucy Cho

Lucy is based in Edinburgh, Scotland and focuses on Good News and Politics for The Borgen Project.

Photo: Flickr

In Ecuador,

In Ecuador,

After

After

Tanzania’s

Tanzania’s