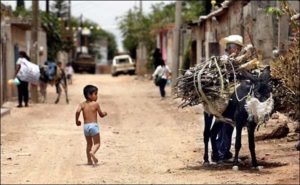

A few weeks ago, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) boarded a commercial flight with constituents on his way to meet President Donald Trump. Many viewed it as a rare presidential moment, considering the poverty rates in Mexico of 52.4 million people living in poverty. However, AMLO has justified his unique transportation method as a small gesture to those in poverty by saving government money.

A few weeks ago, Mexican President Andrés Manuel López Obrador (AMLO) boarded a commercial flight with constituents on his way to meet President Donald Trump. Many viewed it as a rare presidential moment, considering the poverty rates in Mexico of 52.4 million people living in poverty. However, AMLO has justified his unique transportation method as a small gesture to those in poverty by saving government money.

Cause of Rising Poverty Rates

Unfortunately, COVID-19 continues to ravage Mexico’s globally-dependent economy and unequipped health system. Simultaneously, this massive group of people living in poverty is only going to expand. Addressing this growing crisis is not only our humanitarian duty as one of its major allies. Rising poverty rates in Mexico will also inevitably threaten the American people in two key ways.

A Persisting Opioid Epidemic

In 2017, President Trump declared the Opioid Epidemic as a national emergency, citing the rising cases of fentanyl overdose deaths. Despite the domestic focus on the problem, it has become more evident that a solution to save the tens of thousands of Americans dying in this crisis requires us to look to the source of the epidemic– Mexico. According to the acting Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) director, Mexican cartels have been responsible for the vast majority of synthetic drugs entering the U.S., including fentanyl.

Problematically, these cartels have been fueled by rising poverty rates in Mexico. In many places, economic hardship has allowed cartels to thrive. They have used protection and basic necessities as a powerful incentive to recruit historically poor populations. Also, vulnerability within many communities has allowed cartels to grow their influence through hollow gestures of aid. This turns cities towards helping their cause; because of this, despite growing civilian casualties in cartel wars, Mexican cartels have seen massive growth in influence and prowess, allowing for them to grow their opioid trade on the US-Mexican border. In order to minimize the cartel’s fueling of the Opioid Epidemic, the American government needs to do more to fight poverty within Mexico. It also needs to find a long term solution to curb the rooted influence most of these cartels have found.

Growing Human Trafficking Concern

Additionally, rising poverty rates in Mexico have pushed many Mexicans towards other illicit industries. According to the London School of Economics, sex trafficking and exploitation is incredibly profitable. As a result, rising economic inequality has pushed many Mexicans towards this industry.

Many people within Mexico have had no choice but to turn to these alternate industries to survive. This is due to a lack of opportunity. As a result, human trafficking has grown within Mexico, with 21,000 minors falling victim to this horrid industry. This problem is not an isolated one. According to the Human Rights Watch, as a result of this industry, Mexico has become one of the largest sources of human trafficking in cases in the U.S. Simply put, rising poverty rates are only fueling a major threat to the U.S. They hurt women and children alike in one of the world’s most horrid illicit industries. Action needs to be taken in order to curb the rising poverty rates in Mexico that have been paramount in causing this crisis.

Mexico has always been a critical economic and geopolitical ally to the U.S. However, as it falls into a growing poverty crisis, the U.S. cannot turn a blind eye. Luckily, positive progress is being seen. Countless organizations such as Freedom from Hunger, Un Techo para mi País (TECHO) and the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) have all been working to mitigate the crisis. In 2018, the U.S. also pledged $4.6 billion to bolster development in Southern Mexico. By continuing on this path and pushing for even more developmental assistance in the future, we cannot only effectively curb the growing poverty crisis. Instead, we can also provide a more secure America for generations to come.

– Andy Shufer

Photo: Flickr

The COVID-19 pandemic has shoved decades of progress in mitigating poverty at risk and has already led to a great loss of life and long-term socio-economic damage in sub-Saharan Africa. The U.N. Secretary-General states that the global poverty rate is predicted to

The COVID-19 pandemic has shoved decades of progress in mitigating poverty at risk and has already led to a great loss of life and long-term socio-economic damage in sub-Saharan Africa. The U.N. Secretary-General states that the global poverty rate is predicted to  Amid the outbreak of intense political, economic and humanitarian crises in Venezuela, one group of

Amid the outbreak of intense political, economic and humanitarian crises in Venezuela, one group of