Nelson Mandela was a civil rights hero and arguably one of the greatest African leaders in history. He led a resistance movement, spent years behind bars unjustly and served as the president of South Africa. His life’s work was instrumental in abolishing apartheid and improving race relations. Not only was he a champion for justice and peace in his own country but also around the world. In 2009, the United Nations declared July 18th “International Nelson Mandela Day.” An examination of Nelson Mandela’s childhood contextualizes his legacy, both honoring and humanizing the man who contributed to the development of democracy and human rights around the globe. His young years are fascinating and enlightening as he exhibited leadership skills and spirit from an early age in his unique circumstances. Read on to discover the beginning of Mandela’s journey towards liberating millions.

Nelson Mandela was a civil rights hero and arguably one of the greatest African leaders in history. He led a resistance movement, spent years behind bars unjustly and served as the president of South Africa. His life’s work was instrumental in abolishing apartheid and improving race relations. Not only was he a champion for justice and peace in his own country but also around the world. In 2009, the United Nations declared July 18th “International Nelson Mandela Day.” An examination of Nelson Mandela’s childhood contextualizes his legacy, both honoring and humanizing the man who contributed to the development of democracy and human rights around the globe. His young years are fascinating and enlightening as he exhibited leadership skills and spirit from an early age in his unique circumstances. Read on to discover the beginning of Mandela’s journey towards liberating millions.

Born into Royalty

On July 18th, 1918, Rolihlahla Mandela was born into the Thembu tribe in the small South African village of Mvezo, Transkei. Nelson’s birth name, Rolihlahla, is translated to mean “pulling branches off a tree.” His father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, served as chief of the tribe. His mother, Nosekeni Fanny, was Mphakanyiswa’s third of four wives. Collectively, the wives bore Mphankanyiswa nine daughters and four sons. Nelson Mandela was born into a powerful family that was devoted to serving and leading his community. He grew up listening to stories of his ancestors’ bravery in wars of resistance, planting the seeds of courage within him to continue the struggle of bringing his people into freedom.

When colonial authorities denied Mphakanyswa of his chief status, he moved his family to Qunu. When Mphakanyswa died from tuberculosis in 1928, Mandela was only nine years old. He was then put under the guardianship of a Thembu Regent, who raised him as his own son.

A New Name

Nelson Mandela was the first in his family to attend school. He excelled in his learning, and the schools he attended had a fundamental impact on Nelson Mandela’s childhood. At his primary school in Qunu, Rolihlahla’s teacher told him that he would be called “Nelson” from now on. This followed the tradition of giving schoolchildren “Christian names”. This given name would be adopted by Rolihlahla, becoming his lifelong moniker. He continued his education at a Methodist secondary school called the Clarkebury Boarding Institute and Healdtown. Throughout his time there, he performed well in boxing, running and academics.

In 1939, Mandela advanced to the prestigious University of Fort Hare. At the time, it was the sole Western-style higher learning institute for South African black people. The next year, Mandela, along with his fellow peers, was expelled for joining a student boycott against university policies. His lifelong advocacy for peaceful protests began here.

Fleeing to Johannesburg

Mandela returned home after being expelled from college and his guardian, Jongintaba, was furious. He threatened that if Mandela did not return to Fort Hare he would arrange a marriage for him. In response, Mandela decided to escape. He fled to Johannesburg and arrived in 1941. He first worked as a mine security officer, then as a law clerk and finally finished his bachelor’s degree through the University of South Africa. As he furthered his studies, he also started attending African National Congress (ANC) meetings against the advice of his employers. In 1943, he returned to Fort Hare to graduate. He furthered his education and expanded his worldview by studying law at the University of Witwatersrand and it was here that his interest in politics was heavily influenced. He met black and white activists and got involved with the movement against racial discrimination that he would continue for the rest of his life.

As Nelson Mandela’s commitment to politics and the ANC grew stronger, he participated in boycotts, strikes and other nonviolent forms of protest to oppose discriminatory policies. He opened South Africa’s first black law firm, which specialized in legal counsel to those harmed by apartheid legislation. He offered his legal counsel from a low cost to no cost at all. A long struggle was ahead of Mandela to achieve full citizenship, democracy, and liberty for his people. His journey began in his early years as Thembu royalty and in his academic work. Nelson Mandela’s childhood is only the first piece in the remarkable making of an international icon.

– Mia McKnight

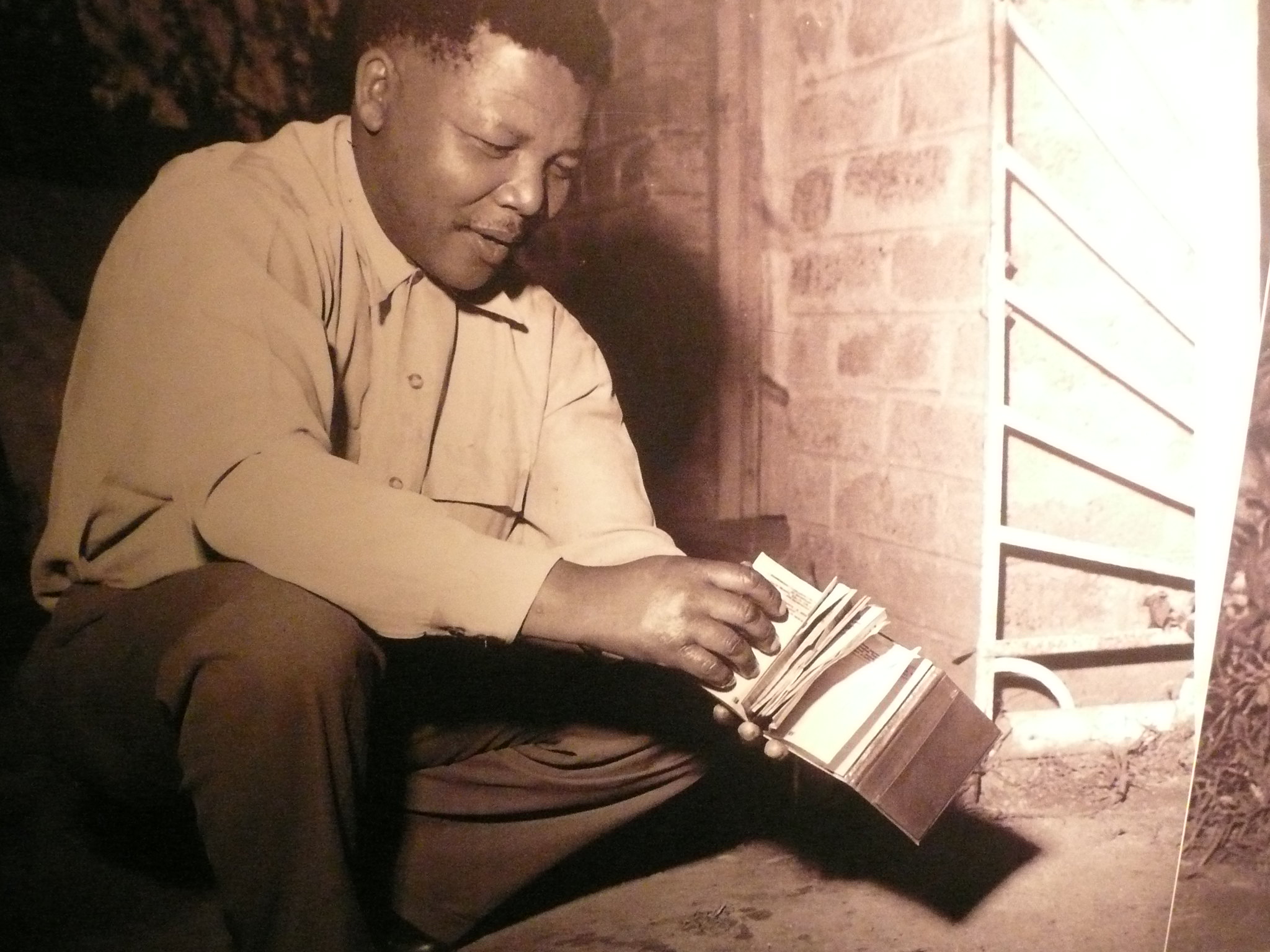

Photo: Flickr

Nelson Mandela’s Childhood

Born into Royalty

On July 18th, 1918, Rolihlahla Mandela was born into the Thembu tribe in the small South African village of Mvezo, Transkei. Nelson’s birth name, Rolihlahla, is translated to mean “pulling branches off a tree.” His father, Gadla Henry Mphakanyiswa, served as chief of the tribe. His mother, Nosekeni Fanny, was Mphakanyiswa’s third of four wives. Collectively, the wives bore Mphankanyiswa nine daughters and four sons. Nelson Mandela was born into a powerful family that was devoted to serving and leading his community. He grew up listening to stories of his ancestors’ bravery in wars of resistance, planting the seeds of courage within him to continue the struggle of bringing his people into freedom.

When colonial authorities denied Mphakanyswa of his chief status, he moved his family to Qunu. When Mphakanyswa died from tuberculosis in 1928, Mandela was only nine years old. He was then put under the guardianship of a Thembu Regent, who raised him as his own son.

A New Name

Nelson Mandela was the first in his family to attend school. He excelled in his learning, and the schools he attended had a fundamental impact on Nelson Mandela’s childhood. At his primary school in Qunu, Rolihlahla’s teacher told him that he would be called “Nelson” from now on. This followed the tradition of giving schoolchildren “Christian names”. This given name would be adopted by Rolihlahla, becoming his lifelong moniker. He continued his education at a Methodist secondary school called the Clarkebury Boarding Institute and Healdtown. Throughout his time there, he performed well in boxing, running and academics.

In 1939, Mandela advanced to the prestigious University of Fort Hare. At the time, it was the sole Western-style higher learning institute for South African black people. The next year, Mandela, along with his fellow peers, was expelled for joining a student boycott against university policies. His lifelong advocacy for peaceful protests began here.

Fleeing to Johannesburg

Mandela returned home after being expelled from college and his guardian, Jongintaba, was furious. He threatened that if Mandela did not return to Fort Hare he would arrange a marriage for him. In response, Mandela decided to escape. He fled to Johannesburg and arrived in 1941. He first worked as a mine security officer, then as a law clerk and finally finished his bachelor’s degree through the University of South Africa. As he furthered his studies, he also started attending African National Congress (ANC) meetings against the advice of his employers. In 1943, he returned to Fort Hare to graduate. He furthered his education and expanded his worldview by studying law at the University of Witwatersrand and it was here that his interest in politics was heavily influenced. He met black and white activists and got involved with the movement against racial discrimination that he would continue for the rest of his life.

As Nelson Mandela’s commitment to politics and the ANC grew stronger, he participated in boycotts, strikes and other nonviolent forms of protest to oppose discriminatory policies. He opened South Africa’s first black law firm, which specialized in legal counsel to those harmed by apartheid legislation. He offered his legal counsel from a low cost to no cost at all. A long struggle was ahead of Mandela to achieve full citizenship, democracy, and liberty for his people. His journey began in his early years as Thembu royalty and in his academic work. Nelson Mandela’s childhood is only the first piece in the remarkable making of an international icon.

– Mia McKnight

Photo: Flickr

International Cooperation in the Fight Against Locusts

Asia, the Middle East and Africa are in a battle with an entity that threatens the food security of 10% of the population. This problem has come and gone before and goes by the name of the desert locust. These locusts fly in swarms of 10s of billions, in coverage ranging from a square third of a mile to 100 square miles. For reference, a swarm the size of one-third of a square mile could eat the equivalent of 35,000 people.

The leading cause of the sudden outburst of locusts is the months of heavy rain that Africa and Southwest Asia had towards the end of 2019. Locusts thrive in wet conditions when breeding and the rain sparked a massive emergence of the bugs.

The locusts could become the cause of food insecurity for millions of people. The reason for this is the sheer number of insects and also how quickly they can travel. They swarm from one food supply to the next, while moving from one country to the next within days. When they decide to land in a town or city that seems to have an abundance of crops, they will eat anywhere from 50 to 80% of all the plants. This has resulted in many countries and international institutions increasing cooperation, as the locusts do not discriminate against which country they deplete of resources. Below are five of the ways that collaboration has developed in the fight against locusts, which highlights the importance of working together during national emergencies.

5 Cases of International Cooperation in the Fight Against Locusts

The cooperation between organizations and countries in the fight against locusts proves to be the silver lining of the infestation. International institutions are effectively planning, tracking and coordinating efforts to minimize the problem for farmers and food-insecure people around the world.

– Aiden Farr

Photo: Pixabay

3 Organizations Fighting Poverty in Kenya

Poverty in Kenya is on the decline. Between 2005-06 and 2015-16, the percentage of Kenyans living under the international poverty line (characterized in 2011 as US$1.90 per day) decreased from 46.8% to 36.1%. Kenyan poverty is currently decreasing by 1% yearly, a rate which is ahead of some countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). Still, the rate of poverty reduction in Kenya falls short of most nations in the lower-middle-income range.

The majority of impoverished Kenyans are in the rural, northeastern regions of the country. In Kenya, only 72% of homes possess viable drinking water. This is 4% above the average in the Sub-Sahara, but below countries like Ghana and Rwanda. In 2015 records showed 84% of Kenya’s population over 14 years of age were literate. This constitutes an 11% increase from Kenya’s 2005 literacy statistics.

While overall poverty in Kenya is decreasing, there is still much that people can do. Here are three of the many organizations creating change in Kenya and SSA more broadly:

The Boma Project

In its mission statement, The Boma Project states that it “empowers women in the drylands of Africa to establish sustainable livelihoods, build resilient families, graduate from extreme poverty and catalyze change in their rural communities.” The Boma Project creates triads of women and provides them with financial support in order to begin and grow their businesses. It also provides these women with two years of mentorship. Currently, 159,684 women and children have received support from The Boma Project.

Daate Inyakh of northern Kenya lives in an area with little access to water and often fought to feed herself and her six girls. In 2014, Inyakh began receiving help from The Boma Project. This gave her the opportunity through training and financial aid to start her own business. Inyakh’s triad is now in charge of their own shop and she is in the process of learning to read.

The Makuyu Education Initiative (MEI)

MEI is a very small nonprofit founded in 2011 that operates in Makuyu, Kenya. The organization provides children of the ultra-poor in this region with the opportunity to “escape the vicious cycle of poverty by fighting malnutrition and other obstacles that can deter them from reaching their full potential.” MEI provides a home for any children in the program, many of whom are orphans. It gives these children holistic support in education, health care and consistent meals. MEI relies on volunteers and donations in order to accomplish its important work.

African Childrens Haven

African Childrens Haven protects some of Kenya’s, Ethiopia’s and Tanzania’s most impoverished children and their families. Primarily, the organization takes care of orphaned children who lost their parents to HIV/AIDS. This organization’s work focuses on girls. African Childrens Haven supports these children by providing scholarships, regular meals and sexual education. It also works to prevent child marriage and sex trafficking. The organization provides its services to more than 700 children.

These three organizations are a few among many addressing the multifaceted reality of poverty in Kenya. Engagement and donation to causes like these provide anyone with a tangible avenue to help make a difference.

– Clara Collins

Photo: Flickr

Reducing Period Poverty in New Zealand

On June 3, 2020, the parliamentary government of New Zealand announced an initiative designed to combat one of the most pervasive but least discussed forms of poverty across the globe; period poverty. The initiative will provide free sanitary products (tampons and pads) through a school-based program in order to alleviate period poverty in New Zealand. The investment will start small in the Waikato region, the 11th poorest region in New Zealand.

What is Period Poverty?

Period poverty exists in nearly every country across the globe, albeit to varying degrees. No matter the location, one could easily find an individual who is struggling to pay for proper sanitary products. One can define period poverty as a lack of access to sanitary products, menstrual hygiene education, toilets, handwashing facilities or proper waste management. Period poverty most commonly exists in developing but isolated nations.

Prime Minister Arden Answers the Call

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern brought the real facts of period poverty to the general public explaining how it affects the women and girls of not only New Zealand but also other countries across the globe. Expectations have determined that the government will roll out a NZ$2.6 million ($1.7 million) program providing free sanitary products through schools across the country. At first, the program will only exist in 15 schools in the Waikato district of New Zealand with plans to expand nationwide by 2021.

While New Zealand does not have a national index to measure the poverty levels of various communities, using a fixed-line analysis showed that roughly 15% of the total population of New Zealand lives in poverty. Similar to other products (unfortunately even medical ones), the price of sanitary products fluctuates fairly rapidly depending on the brand. On average the cost of a package of tampons in New Zealand is roughly NZ$5.50. With women typically having 480 periods throughout their lifetime, that brings the total long-term out-of-pocket cost to NZ$2,640 if the individual only buys Bargen tampons.

Eliminating Period Poverty in New Zealand

The New Zealand government believes that through this initiative, it can begin to cut childhood poverty by half in the next decade. In her speech on June 3, Prime Minister Ardern said that roughly 95,000 girls between the ages of 9-18 miss school and other activities due to a lack of access to proper sanitary products.

One of the perceived and anticipated effects of this program would be to allow children the opportunity to continue with their daily activities despite their period. Providing free sanitary products and education on menstrual health will do just that, all the while ensuring that individuals experiencing period poverty do not have to make homemade tampons and pads out of non-sanitary household items.

Period poverty may not seem like an issue that could possibly affect many people around the globe. However, when considering the data surrounding the situation, 2.3 billion people globally do not have access to clean water and sanitary products. When one throws the price of a single pack of tampons into the equation for countless families struggling to put food on the table, the question becomes whether or not the family in question will be able to eat. Unfortunately, the answer to this question is all too obvious.

Fortunately, New Zealand is not the only country that has put forth legislation to provide free sanitary products. Both England and Scotland have recently written legislation providing free sanitary products through schools. The New Zealand government and the U.K. and Scottish governments have made huge strides in the right direction to provide proper sanitary products to families, taking a direct swing at childhood poverty and the afflictions that come with living in that economic bracket.

Photo: Flickr

10 Facts about Sanitation in Algeria

10 Facts about Sanitation in Algeria

Rural-Urban Divide: Urban Algerians are more likely to have greater access to sanitation than rural Algerians. Three percent more rural Algerians do not have access to basic sanitation (i.e sewers, latrines and septic tanks) than urban Algerians. This rural-urban divide continues when comparing lower classes. Algeria’s urban poor experience 10% more sanitation coverage than their rural counterparts. To help address the challenges associated with rural sanitation, the African Development Bank established the Rural Water Supply and Sanitation Initiative in 2003.

Hand Washing: While the majority of Algerians are able to practice proper hygiene by washing their hands, disparities exist among rural and urban communities. Currently, 83% of Algerians are able to wash their hands. This is slightly higher than what is typical in the region. However, there is a 14% gap between rural and urban Algerians; only 73% of rural Algerians are able to do so.

Recent Improvements: Over the last decade, rural Algerians have gained greater basic sanitation. From 2000 to 2017, basic sanitation coverage increased by approximately 10%. Today about 70% of Algerians have access to basic sanitation. This is relatively high for the region as an average of only 50.2% of individuals have this service region-wide.

Access to Toilets: Similarly, the number of rural Algerians openly defecating has substantially decreased. From 2000 to 2017, this percentage decreased by 12.5%. Today only about 3% of Algerians experience this level of deprivation. This is substantially lower than the regional percentage of 10% of rural individuals.

Rural Sewers: Disadvantaged Algerians have increased access to better sanitary facilities. Since 2000, approximately 14% more poor Algerians gained access to sewers. Notably, this positive trend is true of rural Algerians. Since 2000, 17% more rural Algerians gained access to sewers. Today about 60% of this demographic has sewers.

Regional Access to Sanitation: As a whole, more Algerians have better sanitation facilities. In the last decade, sewer availability has increased by about 14%. Today, about 83% of all Algerians use sewers. This percentage is higher than the regional percent of 58%.

Drinking Water: In 2000, few Algerians had access to quality drinking water facilities. The majority of Algerians gain drinking water from pipe-improved water. Notably, this is true for both rural and urban Algerians. To address this issue, the Algerian government established L’Algérienne Des Eaux (ADE), a public company, in 2001. To further remedy this problem, the Algerian government established a program to create more extensive water pipelines to Médéa, a city in Northern Algeria.

Students: Most Algerian students have access to basic sanitation and safe drinking water. Currently, 98% of Algeria’s primary students have basic sanitation; 87% have safe drinking water. This is a remarkable achievement as regionally only about 8o% of all students have basic sanitation and 74% have safe drinking water.

Drinking Water Improvements: Most Algerians have access to safe drinking water. 93% of Algerians have basic access to drinking water. This is true of both urban and rural areas with only a 7% gap between the two categories.

These ten facts about sanitation in Algeria reveal that Algeria has overcome substantial challenges. While most Algerians have access to some level of sanitation, drinking water and hygiene, there remains a higher risk for waste-related illnesses such as cholera. Furthermore, while there remains a persistent gap between its rural and urban citizens, the country’s overall coverage and sanitary facilities have improved since 2000. With sustained effort by the Algerian government and the African Development Bank, Algeria can overcome the remaining obstacles to better public health.

– Kaihua Tymon Zhou

Photo: Wikimedia

10 Facts About Sanitation in Bhutan

10 Facts About Sanitation in Bhutan

Overall, these 10 facts about sanitation in Bhutan demonstrate that the sanitation, water and hygiene conditions are quickly improving in the country. Initiatives by the government, UNICEF and other nonprofits in the country have led to substantial positive changes. However, inequality in access to improved sanitation services remains a major issue, and Bhutan still has a long way to go to provide improved sanitation throughout the entire country.

– Kayleigh Crabb

Photo: Pixaby

Creative Solutions for Homelessness in Costa Rica

Located in Central America and bordering the Pacific Ocean, Costa Rica is home to approximately 4.5 million people. Flourishing on global exports and the travel industry, many know Costa Rica for its exceptional exports in fruits, vegetables and coffee.

However, as a developing country, Costa Rica struggles from problems with sanitation, poverty and homelessness. More than 1 million Costa Ricans live in severe poverty, and approximately 52% of the population suffers from insufficient and unstable living conditions. Within the last few decades, citizens have emphasized the need to reduce overall homelessness, focusing on urban areas. Here are a few unique ways Costa Rican citizens are attempting to reduce overall homelessness.

Aiding the Homeless

The Chepe se baña project in Costa Rica aims to provide a better life for the homeless. Originating from the Promundo Foundation, Chepe se baña hopes to help around 200 homeless people near San José, the capital of Costa Rica. The name of the project references a large bus that consists of four showers and a ramp for people with disabilities. The bus provides efficient and free sanitation toward people living in poverty. Running on generous donations and private enterprises, Chepe se baña provides much help to the homeless in San José.

Costa Rican communities took matters into their own hands in 2015 when social groups Friends of the World and Vaso Lleno worked to provide relief for the homeless. More than 200 volunteers traveled to urban areas, ranging from Parque España to San José, offering daily necessities such as food, water and clothes. These volunteers were able to offer over 1,500 beverages, more than 18,000 kg of beans and hundreds of items of clothing for men, women and children. Volunteers would pack lunches with sandwiches and drinks, and deliver them to people in need.

While Chepe se bana and hundreds of volunteers may not end homelessness in Costa Rica, the support has certainly provided necessary relief for people who are in difficult living situations. It is important to understand that the acts of citizens do in fact create a noticeable difference when attempting to reduce global poverty.

Friends of Costa Rica

Outside of Costa Rica, an American organization called Amigos of Costa Rica is a nonprofit organization that uses funds to directly address poverty — specifically homelessness — in Costa Rica. Through donations and helpful resources, Amigos of Costa Rica has committed itself to aiding Costa Rica in achieving sustainable development.

Thanks to these and other initiatives, Costa Rica now has the lowest poverty rate in Central America. While Costa Rica continues to struggle to reduce overall homelessness and poverty, efforts to diminish or decrease poverty rates are now showing positive results. With increased efforts to support the homeless population in Costa Rica, overall poverty will likely continue to decrease.

– Elisabeth Balicanta

Photo: Unsplash

5 Facts About Tuberculosis in Côte d’Ivoire

5 Facts About Tuberculosis in Côte d’Ivoire

One important organization is The Stop TB Partnership. By pairing government agencies with other foundations, research agencies and private sector resources, this organization aims to create a TB-free world. In 2014, various partners met with specialists from the Programme National de Lutte contre la Tuberculose to design a national committee tasked with controlling and treating tuberculosis in Côte d’Ivoire. The members of these groups were responsible for designing a plan for infection control, allocating monetary and human resources and outlining the structure of the new committee. Through this workshop, the anti-TB program in Côte d’Ivoire established clear strategies for tackling the problem of tuberculosis. Stop TB developed oversight committees, regulations for how resources are spent and a plan for reducing the spread of TB.

According to the United Nations, Côte d’Ivoire is on the way to reaching various Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The U.N. is actively helping Côte d’Ivoire eradicate illnesses like HIV, malaria and TB by the year 2030 through free doctor visits and accessible medicine.

It is crucial that the citizens of Côte d’Ivoire receive the proper treatment and financial assistance to help them overcome the tuberculosis endemic. It is imperative that those diagnosed with this illness are immediately identified and properly treated. With strategic planning, proper funding and extensive training for medical professionals, the infection rate of tuberculosis in Côte d’Ivoire is expected to decrease in the coming years.

– Danielle Kuzel

Photo: Flickr

Recent Progress: Addressing Poverty in Colombia

Macroeconomic trends show there has been equitable growth in Colombia. While as of 2017, Colombia held the second-highest wealth inequality rate in Latin America, only slightly better than Brazil, it has been on a downward trend since 2000. Additionally, poverty in Colombia dropped by 15% between 2008 and 2017 to a low of 27%. Extreme poverty reduced by half from 2002 to 2014, with more than 6 million people moving out of poverty. This put more Colombians in the middle class than in poverty for the first time. Finally, between 2008 and 2017, the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew at a rate of 3.8%. This is more than twice as fast as the members of the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD).

Problems

However, increasing exports drive much of the recent growth and reduction in poverty in Colombia. Commodity prices have risen significantly over the past several years. This growth is unsustainable, as a recent drop in prices has hindered the export industry. Colombia has also been struggling with such issues as a lack of financial inclusion, low productivity, low-skilled workers and a large informal economy.

The informal economy consists of such jobs as farm workers, taxi drivers and street vendors where “they make no direct tax contributions, have no security of employment and do not receive pensions or other social benefits.” As of May 2014, informal workers made up nearly two-thirds of the Colombian labor force. This means millions do not possess a dependable income. They do not have the opportunity to contribute to or receive a pension fund or other government benefits. For these reasons, the large informal sector is also a big contributor to inequality and poverty in Colombia.

Another major issue holding back Colombia has been its decades-long internal struggle for peace. Nearly a quarter-million Colombians have died from the conflict, with 25,000 disappearances and nearly 6 million displaced. Although a peace agreement was reached in 2016, tensions are still high in the country between the government and the rebel militia.

Solutions

Nonetheless, steps are occurring to ensure that Colombia is able to continue its recent progress. With nearly 6 million people displaced because of the internal conflict, land restitution is a key step to make. With the help of the World Bank, 1,852 land restitution legal cases occurred by the end of 2014. Additionally, the World Bank helped the Colombian government give reparations to those the conflict affected, with a focus on Afro-Colombian and indigenous groups who the conflict disproportionately affected.

Some are using digitalization and technology to help formalize businesses by simplifying the registration process and making tax collection more efficient, enabling businesses and individuals to pay taxes and contribute to the pension system and providing them access to many social benefits. Digitalization also provides greater access to financial services. This is occurring by providing micro-credits, expanding the outreach of banking services, lowering the cost of financial services and simplifying electronic payments.

USAID’s Role in Poverty Reduction in Colombia

The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) has also helped decrease poverty in Colombia by increasing the presence of democratic institutions in the country. Through this, the USAID hopes to “foster a culture of respect for human rights, promote access to justice, increase public investment and provide services to historically underserved and conflictive rural areas.” This organization fights for inclusive growth and encourages investment in rural areas. Additionally, it helps producers expand their market, provides financial services and helps restore the land to its original owners before the conflict.

All of these efforts and many more are helping reduce poverty in Colombia. The goal is to keep the country on a path toward equitable and inclusive development that leads to a reduction of inequality.

– Scott Boyce

Photo: Flickr

Uganda’s Water Crisis and the Economy

What Uganda’s Water Crisis Looks Like

Although Uganda experienced three decades of a growing economy, almost 40% of Ugandans still live on less than a dollar a day. In addition to its history of poverty, many people in Uganda struggle to find clean water. Traditionally, communities with high poverty rates rely heavily on natural water sources because they lack the technology to build wells and plumbing. The lack of clean water sources in impoverished communities propels the cycle of poverty.

A video by a global relief organization called Generosity.org documents the lives of Ugandans who struggle to find clean water. The video features a Ugandan mother, Hanna Augustino, who spends three hours a day getting water for her family of nine. Hanna explains that the water is so dirty it has worms and gives them diseases like Typhoid Fever. However, when the family gets sick, they cannot afford to go to the hospital. The lack of clean water in an already impoverished community leads to disease. In 2015 Uganda experienced a Typhoid Fever outbreak that was mainly due to contaminated water sources. For many in these communities, medical care is unaffordable. The water crisis causes a need for medical care for a treatable disease. The need for more medical care creates more financial hardship on families already struggling in poverty.

Economic Impacts

In addition to disease, collecting water is very time-consuming. In some areas like Hanna’s, it can take hours to retrieve water. People spend hours getting water instead of working to provide income for their families or as caregivers themselves. Water retrieval is another aspect of the water crisis that negatively impacts local economies and continues the cycle of poverty.

Farmers are some of the most negatively impacted by the water crisis. Farming and agriculture make up a large part of the Ugandan economy. Poverty-stricken communities need water sources for irrigation and farming, which some families rely on as a household income. About 24% of Uganda’s GDP comes from agriculture. This portion of the economy is dependent on clean, accessible water sources. Without clean water sources, farmers’ animals and crops would die. Without farmers, local communities would have no food. As a result, farmers are an important local resource for local communities and an important cog in local economies.

A Helping Hand

Despite the rippling effects of the water crisis, there are many organizations working to alleviate the crisis. For instance, Lifewater is an organization that funds “water projects.” These projects build clean water sources for villages that have none. Lifewater is currently funding 220 water projects in Uganda alone. If you are interested in learning more about Lifewater, you can go to their website at Lifewater.org.

Lifewater is one of many organizations working to provide villages in Uganda with clean water. Along with being essential to human life, water can affect many different aspects of daily life. Spending hours fetching water or drinking dirty, disease-ridden water can negatively impact the local economy. Any negative impact on the economy is especially devastating for communities already affected by poverty. Like Lifewater, there are many organizations bettering local economies through their clean water efforts.

– Kaitlyn Gilbert

Photo: Flickr