The UN’s Role in the Haitian Cholera Outbreak of 2010

The Haitian cholera outbreak in 2010 became endemic, after at least a century of the disease not posing a threat.

Spread through contaminated water, the infectious disease causes dehydration and severe diarrhea. It can even lead to death if left untreated, sometimes in just a few hours. The outbreak transpired just after a fatal earthquake occurred in the country.

The United Nations (U.N.) sent peacekeepers to Haiti to help with the damage but failed to screen them for cholera or build them sufficient toilet facilities. As a result, cholera-infected wastewater flowed into Haiti’s main river — a main source for washing, cooking, cleaning and drinking. By 2011, over 470,000 cases of cholera were reported, with 6,631 connected deaths.

Immediate Response

Within days of the Haitian cholera outbreak, the Ministry of Public Health and Population (MSPP), along with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and its partners, established a national surveillance system to track cases of the disease.

Treatment and prevention materials were also quickly developed, and thousands of healthcare workers were trained. Together, the organizations reduced the initial mortality rate of four percent to less than one percent, saving an estimated 7,000 lives.

However, thousands of people continue to become sickened each year by cholera. Haiti’s water and sanitation infrastructure require major improvement for any significant, long-term progress to be made.

The U.N.’s Reaction

After denying any responsibility for over five years, the U.N. has now officially admitted to a role in the Haitian cholera outbreak.

The deputy spokesman for the Secretary-General, Farhan Haq, recently sent out an email saying, “over the past year, the U.N. has become convinced that it needs to do much more regarding its own involvement in the initial outbreak and the suffering of those affected by cholera.” He wrote that a “new response will be presented publicly within the next two months, once it has been fully elaborated, agreed with the Haitian authorities and discussed with member states.”

Although this statement fails to put blame on the U.N. or to indicate a change in its legal position — that it is absolutely immune from legal actions — it does represent a significant step forward for the U.N.

Looking Forward

Haiti launched a National Plan to eliminate cholera from the country in 2013. The 10-year-long plan focuses on water and sanitation, health and preventing further infections.

However, the plan is terribly underfunded. The U.N. Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) pledged over $125 million toward this program, $19 million of which was received; the plan is anticipated to top a total of $2.2 billion in investments.

Nigel Fisher, Special Representative of the U.N. Secretary-General in Haiti said, “It’s a big challenge. We have to raise literally billions of dollars. And this requires sustained support and commitment. That’s what we are here for. We, all of us partners, have a moral obligation to stay the course with cholera. Not just to lower the incidence of cholera, but to eliminate it from Haiti.”

– Alice Gottesman

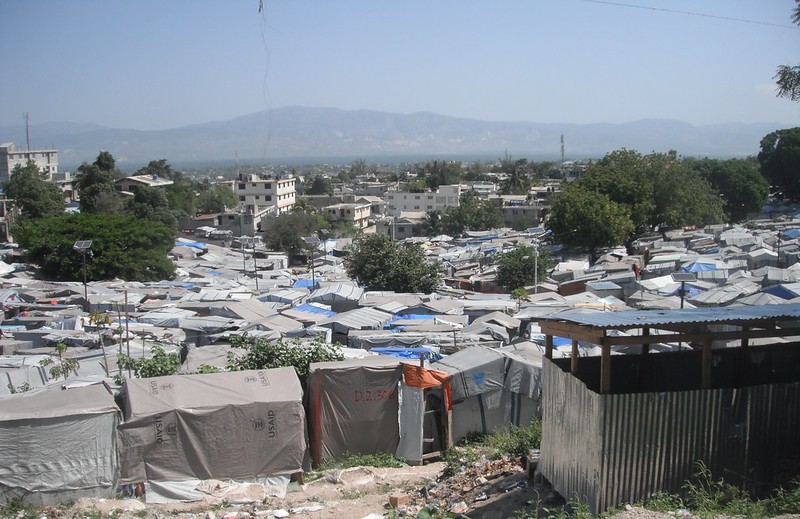

Photo: Flickr