Solving the Conflict Diamonds Crisis

“‘Diamonds are forever,’ it is often said. But lives are not. We must spare people the ordeal of war, mutilations and death for the sake of conflict diamonds,” once insisted Martin Chungong Ayafor, Chairman of the Sierra Leone Panel of Experts. Although the world has come a long way since the development of various campaigns against blood diamonds, the most prominent being the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), the current measures in place are not effective enough and must be modified, as expressed by Global Witness.

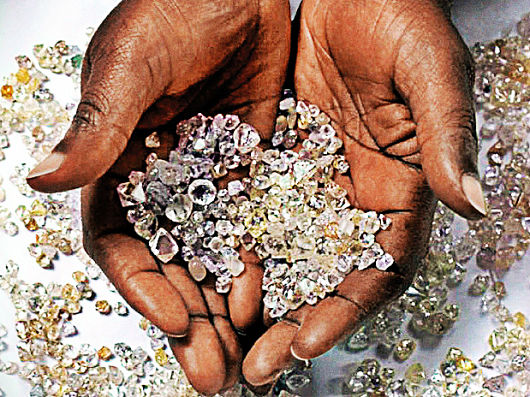

Conflict diamonds are diamonds that originate from areas controlled by rebel forces opposing legitimate governments. These rebels use diamond profits to fund their military actions, keeping them in power. The struggles to keep a hold of these diamonds often involve torture and murder, and can lead to forced labor of civilians. Conflict diamonds have been most prominent in the Ivory Coast of Africa, but have also been apparent in other areas.

Currently, the United Nations and various humans rights groups are working to keep conflict diamonds from entering the worldwide diamond trade. In 2003, they adopted the KPCS, which requires certification of the legitimacy of the mining, production, selling and exportation of the diamonds from every nation. The KPCS also encourages customers to insist upon documentation of the legitimacy of their purchases.

While 71 countries and over 99% of the worldwide diamond trade are covered by the KPCS, the scheme does not involve a treaty. Rather, governments involved must pass national legislation promising not to trade diamonds with any country outside of the KPCS and accept any shipments sent without proper certification. Although moderately effective in a few select areas, there are still countries that the conflict diamond crisis continues to tear apart. The KPCS fails to put a halt to diamond conflicts throughout the world mainly because of its poor decision-making process and weak internal controls on its participants.

The KPCS decision-making process requires consensus. Because of this, just one participating country can block the rest of the countries from moving forward in solving the crisis. This inability to reach consensus causes the lack of management over important issues and lowest common denominator decisions. Consequently, countries are never suspended or expelled, even when clearly violating the basic policies of the scheme. As shown in The Independent, despite evidence of Venezuela’s diamonds being smuggled, Guinea’s 500% increase in diamond production each year and Lebanon’s exportation rate being higher than its importation rate, no action has been taken against any of these countries.

While participants in the KPCS are required to have a system of internal controls, each participant is allowed to decide how to actually keep conflict diamonds from entering world trade. As demonstrated by VERIFOR, the weakness of the internal controls systems of countries such as Armenia, Zimbabwe, and Brazil have highly contributed to the failure of the KPCS in stopping diamond conflict. In studies conducted in Armenia, Global Witness found that the country, which has no internal source of diamonds, allows conflict diamonds to enter world trade because of a governmental lack of oversight in cutting and polishing centers. Rough diamonds can easily be smuggled into factories and no longer fall under KPCS control once they are polished in the centers.

While Armenia’s legislation acts in accordance with the KPCS, there is a lack of internal controls systems in the country when it comes to the KPCS, easily allowing smuggling in and out of the polishing and cutting factories. The Gemstone and Jewelry Department (GJD), Armenia’s Kimberley Process Authority, does not have policies to verify the figures or the movements of polished diamonds, for Armenian tax officials disclose this information. The GJD performs physical inspections of some cutting and polishing companies, but it informs the companies of these visits prior to the actual inspections. This gives the factories the opportunities to prepare for these visits, with ample time to hide or get rid of any diamonds that could stimulate concern among the GJD officials.

This has propelled theories that Armenia has provided diamonds to Nagorno-Karabakh, which is not covered by the KPCS. If this is true, Armenia is violating KPCS standards. Similar situations have occurred in other countries. In order to control situations like these, the KPCS must require a strict system of internal controls in which the government must oversee the values and movements of diamonds in polishing and cutters centers. Companies that cut and polish diamonds must also become more involved in the KPCS.

In order to make the changes necessary to make the KPCS more effective, it is essential to establish a central body of knowledge in each KPCS participant’s government. These central bodies must oversee the movement of rough and polished diamonds and compare these numbers with the diamonds originally mined and imported in the country. Stricter definitions and amendments must also be added to the actual KPCS core document; the main goal of the KPCS to preserve human rights must be expressed clearly.

There has been success in the blocking of conflict diamonds from entering world trade since the implementation of the KPCS. Consumers are currently more conscience of the issue and often think about this while purchasing diamonds, as many major jewelry companies offer documentation of the legitimacy of the diamonds. There has also been success involving monitoring and the peer review mechanism of the KPCS. Despite the minor successes of the scheme, the KPCS evidently still has a long way to go regarding its reforms and policies.

– Arin Kerstein

Sources: Global Policy 1, Global Policy 2, Global Witness, Institute for Human Rights and Business, The Independent, United Nations

Photo: Kaia Joyas