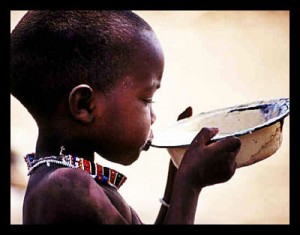

Rethinking Hunger in Africa

Philanthropists may be tempted to rejoice that recent trends have shown that the total number of people who face chronic hunger has dropped. New surveys, however, caution those working to eradicate global poverty.

The Afrobarometer is an independent, nonpartisan research project that measures the social, political and economic environment in Africa through a series of regularly-repeated surveys. By consistently asking the same, standard set of questions in more than a dozen African countries each year, the Afrobarometer can track trends in public attitudes that can be shared with various public actors in order to create better dialogue between the public and the government.

When asked in a recent Afrobarometer survey how many times in the past year they had gone without food, 16% of survey participants responded either “always” or “many times.” Even as global instances of chronic hunger drop as a whole, Africa remains the exception to the trend. The U.N. suggests that 239 million African citizens, or nearly 23% of the total African population, meet the U.N.’s criteria for being chronically undernourished.

The situation is even more alarming when one considers that chronic hunger mainly affects African children, who may experience stunting (low height), wasting (low weight) or micronutrient deficiency if exposed to chronic hunger conditions between the ages of 2 and 3. Chronic hunger not only puts children at risk for future health complications but can also impair future economic concerns as well. Studies have also shown that undernourished children eventually earn an average of 20% less than their healthy peers.

The current hunger problems in African can be traced back to a reliance on maize. Though maize is highly caloric, it offers mediocre nutritional qualities and thus can exacerbate malnutrition even as it satisfies daily caloric needs. Both Zambians and Malawians report receiving more than 50% of their calories from maize.

Over-reliance on maize is not just stunting the growth of African children, but also the potential of the African economy and agricultural development. By only producing maize, African farmers limit their access to global markets, thus making them too reliant on foreign aid and capital.

Instead of maize, the U.N. and its associated nutritionists suggest a food fortification program that supplies rural grain mills with a range of foods that include added iodine, zinc and vitamin A to provide an extra nutritional boost. Additionally, initiatives like ReSCOPE are using schools and colleges in Africa to teach a technique called permaculture, which uses a version of organic farming to keep nutrients in the soil to promote sustainable, year-round crops that will help local farming cultures flourish like never before.

These initiatives follow the concept of the “teach a man to fish” proverb. By promoting a culture of food self-sufficiency that allows African farmers to create both the quantity and quality of the food needed to meet their local nutritional needs, global aid communities and governments may be giving Africa the long-overdue ability to stand on its own two feet.

– Alexandria Bruschi

Source: Afrobarometer.org,Think Africa Press

Photo: WPHR