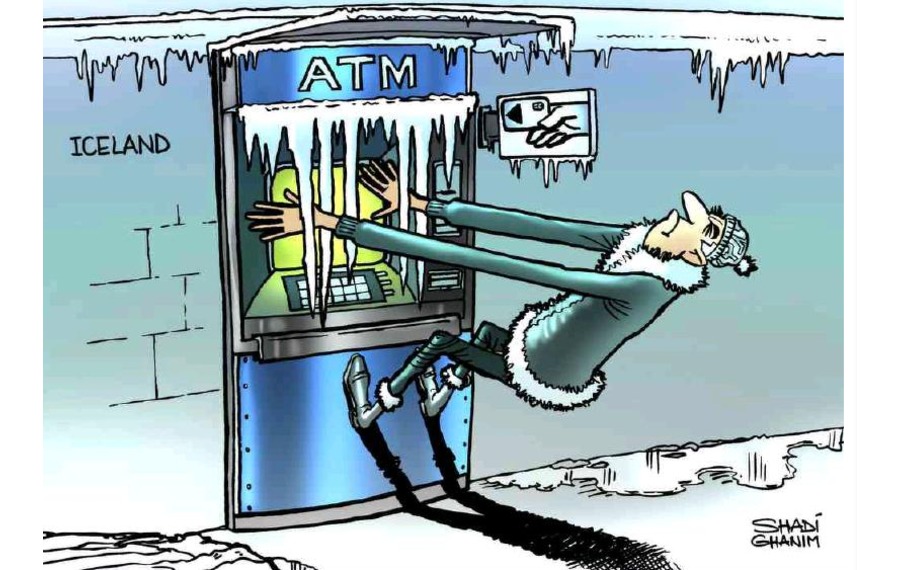

What Iceland Can Teach Us about Financial Recovery

During the financial crisis seven years ago, while many countries were struggling to stay afloat, Iceland was already at the bottom of the sea. A tiny country with a population of only 320,000, Iceland experienced near-total bank failure in the span of three days and a 95% decrease in stock. While monetary policies in the United States and Europe let large amounts of cash flow into the economy, Iceland let enormous amounts of dollars flow through. When the Icelandic krona crashed in 2008, the country’s three biggest banks had amassed wealth more than 10 times the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). As a result of this “loose money” policy, 85% of the economy tanked. The lack of cash flow regulation in the economy led to its downfall and hindered the rebuilding process.

Iceland’s attempts at becoming an international banking powerhouse also factored into its demise. With very high interest rates, international investors could borrow dollars at 5%, exchange them for krona, and buy Icelandic stock at 9% interest. They would profit off the difference in interest rates. Without any governmental controls on the flow of money, all cash could have exited the country, further depressing the economy. However, with help from the International Monetary Fund, the Icelandic government began to impose strict capital controls, barring krona from leaving the country or residents from buying foreign currency or international stock. In the years immediately following the crash, the government raised taxes and provided debt relief to mortgage holders, but not to social services.

It also did something most developed countries have failed to do: jail bankers.

International hedge funds purchased claims for pennies at the height of the crash. Once financial recovery started, their assets grew, giving them a large share of power over the financial system. Due to continued cash control policy, this control affected the lives of Iceland’s residents as well. Residents were especially limited in the amount of foreign cash they could spend, which became a problem when traveling abroad or investing in international stock. “You have a feeling that there’s a system watching you and telling you what you can do with your money,” noted Gudmundur Kristjansson, a fisherman.

However, cash flow restriction and the devaluation that resulted posed some benefits for the economy as well. Exports became cheaper and imports more expensive, allowing residents to produce more goods rather than depend on foreign manufacturers. Devaluation caused wages to fall, so unemployment did not reach the soaring heights it did in Europe. Tourism increased as more people began to travel to Iceland for its cheap prices and its currency independence from less developed European countries.

However, the bars that once held Iceland in restricted success must soon be lifted. “We are enjoying the longest sustainable growth period in recent history,” commented Minister of Finance Bjarni Benediktsson, but cited lacking international investment and competing foreign companies as reasons for lifting the restrictions that helped foster the country’s success for so many years. “[Such controls] are not a sustainable situation for an economy,” said Prime Minister David Gunnlaugsson.

Today, unemployment in Iceland is at 4%, GDP is expected to grow by 4.1% in 2015, and tourism is a flourishing industry. Despite the uncertain future of the country’s economy, it is certainly faring better than other European countries that suffered under the crash. For Greece, whose citizens voted against a deal with creditors and potentially face a future of exiting the Eurozone and financial security, tight monetary restrictions would not be a likely solution. It has a population of 11 million to Iceland’s 320,000, and a GDP 16 times that of the tiny island. When Iceland was preventing its people from spending money, Greece was throwing it around in all directions. Yet Iceland serves as an example of how unorthodox financial practices—controlling the cash flow, granting influence to international hedge funds—can unfreeze a nation and help it rebuild. Restoring a country to financial security is a process of understanding its government, citizens and industries. For Greece and other struggling countries, it will be a struggle, but not a failure.

– Jenny Wheeler

Sources: IMF, New York Times

Photo: The Automatic Earth