Fixing Favelas: Urban Housing Problems in Brazil

Brazil’s booming economic growth is now slowing down, and the rose-tinted glasses have come off, as urban housing problems in Brazil worsen. While the country experienced extraordinary economic growth in the past decade, growing 4 percent per year between 2002 and 2008, these rates have fallen to just 1.3 percent over the past 4 years. If anything, this decline should prompt investigation beyond the pristine beaches and sleek high-rises that have given Brazilian urban life a glamorous aura.

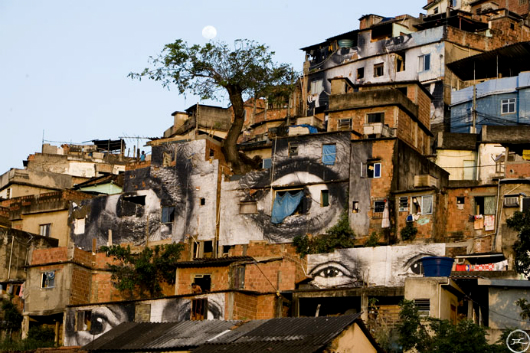

Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, the two biggest cities in Brazil, with populations numbering approximately 11 million and 6 million respectively, have, in particular, captivated international travelers with increasing prosperity and abundant cultural amenities. With more perceived opportunities and advantages in urban areas, Brazilians themselves have also flocked to these two metropolises in search of better lives with 80 percent of Brazilians now living in urban areas. While these ascending cities seem to have garnered attention for all the right reasons, they also contain considerable eyesores; ostracized to the outskirts or huddled in the heart of downtown, dense slums, or favelas, stifle Brazilian cities.

As urban areas have grown, these shantytowns of old tin and cinderblock have come to house millions of impoverished Brazilians in dangerous, crowded and dirty conditions. Though synonymous with Brazil’s urban housing crisis, favelas are nothing new.

They first appeared in Rio de Janeiro around the turn of the 20th century as civil war veterans returned home without government assistance. Turning to the steep hills of Rio de Janeiro’s fame, they sought shelter in makeshift housing, but instead only found more strife in unsafe living conditions. The favelas continued to expand in Brazilian cities as migrant workers settled in Sao Paolo and Rio in search of opportunity and failed to find adequate housing. In Rio, favelas concentrated next to affluent communities and followed the impoverished up the sharp slopes, while in Sao Paolo the favelas formed on the margins of the city. Over the years, a lack of public services and precarious sitting has literally eroded communities as mudslides 1966, 1996 and 2001 wiped away favelas.

Today, favelas have become an unfortunate and noticeable part of Brazilian life, indicative of an overwhelming housing crisis. According to the New York Times, in just the past six years housing prices in Sao Paolo have “increased by 208 percent and the cost of rent has increased by 97.5 percent in the metro area.” The price of a 970 square foot apartment in Sao Paolo is 16 times the average annual wage while nearly a third of the city lives in slum-like conditions. Overall, Brazil has a housing deficit of 7 million units and 20 percent of its total population lives in inadequate housing.

Those who have resigned to these slums must essentially live without infrastructure. Most favelas lack effective sewage systems, access to potable water and waste management systems. The communities have become so densely built up, that modern roads and utilities are nearly impossible to install. As areas with little government regulation, favelas also serve as ideal crime havens. Drug dealings and gang violence plague these secluded streets and have proven notoriously hard to snuff out. In the late 90s, the homicide rate in the Diadema favela of Sao Paulo averaged one murder per day.

Obviously, confronting the issue of the favela has become a daunting task. The Brazilians learned early that the most effective strategy was, ironically, to leave them standing. In the 1980s, after years of demolition, the Brazilian government realized that slum upgrading was more humane and cost-efficient than rebuilding them.

In order to transform favelas into safer, and more hygienic communities, the city officials of Sao Paolo and Rio de Janeiro have employed a surprising set of methods. Despite their squatter’s status, government plans have attempted to provide favela residents with titles to their homes. Not only does this provide the impoverished with dignity, but it also allows the cities greater regulation of the favelas. Along with increased property rights come building safety codes, taxes and public services and utilities that can benefit the community.

These programs have also empowered the communities to assist in the improvement efforts themselves. In Rio de Janeiro’s neighborhood of Providencia Hill, garbage and litter have become pressing issues due to narrow streets that restrict waste management vehicles. A new program has incentivized local trash collection by allowing residents to exchange one bag of trash for a gallon of milk. Not only does this clean up the community, it also provides the residents with better nourishment.

Community engagement also extends to crime prevention. In Sao Paolo, the city government has attempted to attack crime in some of its most dangerous favelas by instituting another form of an exchange program. This time, however, it involves toys. In exchange for toy guns, the program would provide children with comic books in an effort to diminish gun culture and in turn to encourage parents to relinquish their actual firearms. Over the course of three years, 27,000 toy guns have been exchanged along with 1,600 guns in just the first six months of the program.

By employing creative and engaging strategies, government officials from Brazil’s two largest cities have begun to change Brazil’s poor urban housing conditions one comic book at a time. While perhaps eyesores, the favelas have become deeply entrenched communities that are better off upgraded than demolished. Sao Paolo and Rio de Janeiro hold the hopes of millions of Brazilians within their limits. But the question remains: can they house them?

– Andrew Logan

Sources: Cal Poly, The Economist The Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, The New York Times University College London, UN The World Bank

Photo: Wooster Collective