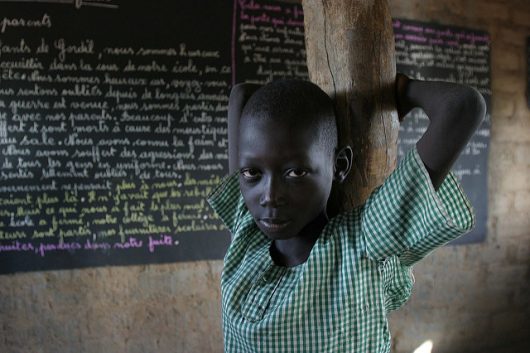

The Guidance for Developing Gender-Responsive Education Sector Plans began in January 2017. It is a dual effort by the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative and the Global Partnership for Education. UNICEF also supports the project.

The Guidance for Developing Gender-Responsive Education Sector Plans began in January 2017. It is a dual effort by the United Nations Girls’ Education Initiative and the Global Partnership for Education. UNICEF also supports the project.

The multicomponent document has roots in the United Nations’ 2015 Sustainable Development Goals (SDG).

The fourth goal, in particular, focuses on changes in education. The SDG outlines 17 goals for improving global education and eradicate factors that compromise academic opportunities for men, women and children in developing nations by 2030.

The Guidance for Developing Gender-Responsive Education Sector Plans aims to cultivate gender equality by implementing and enforcing gender-sensitive policies in schools and other learning environments. It also intends to target both country-level and global and regional-level actors.

The Guide consists of nine interwoven modules grouped into four major categories: Gender Framework, Gender Analysis, Plan Preparation and Plan Appraisal. Here is a summary of the nine modules:

- Module 1: Gives educators the opportunity to set or reconfirm credible gender-responsive goals based on vision and viability

- Module 2: Understanding the legal, political, social and economic makeup of a country and how these variables affect gender inequalities in the educational system

- Module 3: An analysis of current education policies and how the resulting achievements and drawbacks can be used to improve future approaches to policy advocacy

- Module 4: Understand gender-disparity in education based on quantitative and qualitative data

- Module 5: Understanding the local government’s capabilities in addressing gender equality in the educational system

- Module 6: Involving all stakeholders in the planning process to ensure engagement and accuracy in future planning

- Module 7: With reference to modules two through six, develop practical guidelines for the implementation of strategies for addressing gender inequalities

- Module 8: Comprehending the cost involved in implementing the proposed strategies and making informed decisions with funding in mind

- Module 9: Fully understanding how gender inequalities in education are evolving and how to ensure the success of education sector plans in the future

These modules combine to outline a plan that aims to level the playing field and neutralize the current gender disparity in educational outlets in developing countries.

The Guidance for Developing Gender-Responsive Education Sector Plans are currently implemented in Eritrea, Guinea and Malawi. If they prove successful, perhaps these initiatives will continue worldwide.

– Sloan Bousselaire

Photo: Flickr

A small South American nation of fewer than

A small South American nation of fewer than  It can be difficult to appreciate the effects of preventative measures, as many of their benefits are not always easily visible. In the case of vaccines, the benefit, although important, is simply that people do not get sick – which may not seem as outwardly impressive to many as it should. Assessing the economic and health advantages of vaccines remains a necessity for very clearly displaying the immense rewards of implementing vaccine programs.

It can be difficult to appreciate the effects of preventative measures, as many of their benefits are not always easily visible. In the case of vaccines, the benefit, although important, is simply that people do not get sick – which may not seem as outwardly impressive to many as it should. Assessing the economic and health advantages of vaccines remains a necessity for very clearly displaying the immense rewards of implementing vaccine programs.

Located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans is the world’s largest island, Greenland. Ironically, it is also the least populated country in the world, with about 57,728 people as of July 2016. Nevertheless, it is not safe from the problems that plague the world today. The Central Intelligence Agency reports that

Located between the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans is the world’s largest island, Greenland. Ironically, it is also the least populated country in the world, with about 57,728 people as of July 2016. Nevertheless, it is not safe from the problems that plague the world today. The Central Intelligence Agency reports that  As students around the world return to school, there are those who will spend their bitters winters in makeshift shelters. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNESCO), about 123 million or

As students around the world return to school, there are those who will spend their bitters winters in makeshift shelters. According to the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNESCO), about 123 million or