With support from the World Bank Group, the governments of Kenya and South Sudan, as well as other stakeholders, recently inaugurated a new project that will upgrade a critical trade route connecting the two countries.

The updated route will make trade easier between the two countries, improve livelihoods for people living in the northwest region and alleviate regional poverty.

Currently, the Kenya-South Sudan highway, which runs through Trans Nzoia, Turkana and West Pokot counties, is a rugged track. It’s hard for vehicles to pass the deteriorated area.

Travelers run the risk of encountering bandits along the route and also pay fares that are an average of six times the price for a comparable distance on good roads.

The East Africa Transport, Trade and Development Facilitation Project will rehabilitate a 309-kilometer trek of land to create a safe route for goods and people along the Lokichar, Nadapal/Nakodoc road in the northwest region of Kenya.

The World Bank Group launched $500 million to support other activities designed to improve the livelihoods for those living in the region and to improve regional competitiveness.

Diarietou Gaye, World Bank country director for Kenya, says, “This new project is unique in its own right, because of its size, geographical coverage, and the range of activities it will undertake, targeting the specific needs of the vulnerable communities in Trans Nzoia, Turkana and West Pokot counties.”

Including 1.5 million people, those counties are home to some of the country’s poorest and most vulnerable people.

The rehabilitation of this section will cost $676 million, among which the Kenya government will contribute $176 million. Other development partners, such as the African Development Bank, German Development Bank and the European Union have shown interest in financing the reconstruction of the remaining sections.

The World Bank Group, with other development partners such as the African Development Bank and China, will support $80 million for the other 400-kilometer section in South Sudan, from its capital Juba to the border with Kenya.

In addition to rehabilitating the trade and transport corridor, the project will facilitate the construction of a 1,000-kilometer fiber optic connection between Kenya and South Sudan, as well as a one-stop border post to facilitate cross-border transport and trade between the two countries.

When the corridor is upgraded, traveling and sending goods from Kenya’s Port of Mombasa to Juba will be much faster.

Moreover, the project will also offer water and sanitation services, build domestic and export markets for livestock, agricultural produce, fisheries and mineral products, and facilitate extraction of petroleum resources in the recently discovered oil fields in Turkana and neighboring counties.

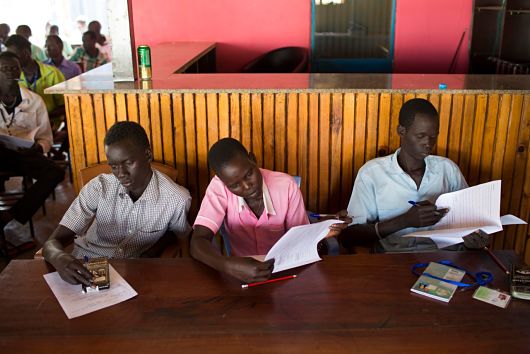

In addition, the project will create jobs and income opportunities for members of the local communities.

– Shengyu Wang

Sources: The World Bank, Chr. Michelsen Institute

Photo: Flickr

The Republic of

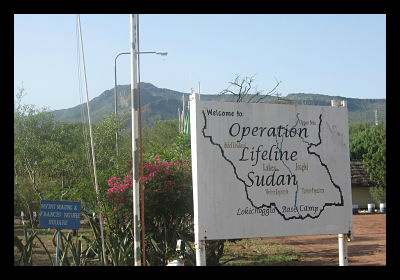

The Republic of  Since the onset of ethnically-motivated conflict within South Sudan in December 2013, an estimated 150,000 South Sudanese civilians have fled the violence to neighboring

Since the onset of ethnically-motivated conflict within South Sudan in December 2013, an estimated 150,000 South Sudanese civilians have fled the violence to neighboring