The United Nations’ Millennium Development Goal (MDG) Five, improving maternal health, has two components: First, reduce maternal mortality by two-thirds between 1990 and 2015, and second, achieve universal access to reproductive healthcare by 2015. Eritrea is one of the few countries in which these goals were fully achieved.

The maternal mortality ratio—which the U.N. defines as “the ratio of the number of maternal deaths to the number of pregnancies,” calling it “an indicator of the risk of dying that a woman faces for each pregnancy she undergoes”— was 1,700 deaths per 100,000 births in Eritrea in 1990. The goal for 2015 was to cut that number to 425 deaths per 100,000 births. In 2013, Eritrea not only met but surpassed this goal, with a maternal mortality rate of just 380 deaths per 100,000 births.

Eritrea saw almost as much success in its efforts to achieve universal access to reproductive healthcare. In 1991, just 19 percent of women had any prenatal care. By 2013, that number had risen to 93 percent, a nearly fivefold increase.

What Has Worked

From 1990 to 2015, maternal mortality declined 45 percent globally and 49 percent in Sub-Saharan Africa. Although this is a marked improvement, it is still considerably less than the MDG goal of a two-thirds decrease. As such, many are wondering what contributed to Eritrea’s huge successes.

Since the establishment of the MDGs, the government of Eritrea has been committed to engaging all people with its new development programs. It strove (and continues to strive) to build a national healthcare system that offers universal coverage that truly does reach everyone, no matter how poor or remote.

Efforts by the government, the U.N. and NGOs working to improve maternal health in Eritrea have reflected this emphasis on the universal and the importance of reaching all Eritrean women. Clinics that are mobile and transitory pop up in a community temporarily, and, after a period of time, move on to the next town. This allows more women to receive healthcare without necessitating more resources or medical personnel.

Empowering Women

Likewise, there has been a strong focus on improving gender equality in Eritrea. The government has outlawed both child marriage and female genital mutilation and is continually working to promote gender equality in education and in the labor force. Today, it is estimated that women in Eritrea make up between 35 and 45 percent of the workforce. This means that women are more visible, more engaged in society politically and socially and better able to advocate for their rights.

Despite Eritrea’s considerable successes, challenges remain for the East African nation. Eritrea has a long history of violence. After 30 years of brutal civil war, it gained independence from Ethiopia in 1993. Conflict with Ethiopia resumed between 1998 and 2000 and, even during times of peace, Eritreans live until a strict authoritarian government. Continued improvements in maternal health in Eritrea will be predicated upon future peace and stability in the region.

The Future of Maternal Health in Eritrea

Access continues to be the main challenge. Women who lack money often struggle to find affordable healthcare. Despite the efforts of mobile health clinics, antiquated infrastructure, old roads and limited public transportation opportunities mean that traveling to a clinic still proves difficult for many women.

Furthermore, although 93 percent of women received at least some prenatal care in 2013, only 55 percent of women had a trained medical professional at their child’s birth. That is a huge improvement from 1991, when only 6 percent of babies were born under the care of a medical professional, but room for improvement remains.

Eritrea’s success in reaching and surpassing MDG Five ought to be applauded. Other countries should follow its example and commit to focusing on universal access to maternal and prenatal care. Despite considerable success regarding lowering the maternal mortality rate and achieving near-universal access to reproductive healthcare, Eritrea should continue to strive to increase the accessibility of healthcare. Eritrea, and the global community supporting women’s health and equity there, can continue to improve the availability of and access to affordable maternal and prenatal healthcare.

– Abigail Dunn

Photo: Flickr

A nation that has been in political turmoil since its independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola has had major concerns formulating a stable, unified country free of conflict. Despite it being Africa’s second-largest oil exporter and producer behind Nigeria, poverty has plagued the nation that has suffered internally due to political corruption, instability and other factors. So, why is

A nation that has been in political turmoil since its independence from Portugal in 1975, Angola has had major concerns formulating a stable, unified country free of conflict. Despite it being Africa’s second-largest oil exporter and producer behind Nigeria, poverty has plagued the nation that has suffered internally due to political corruption, instability and other factors. So, why is

Kazakhstan is a Eurasian country, bordering China and Russia, whose size is comparable to that of western Europe. Kazakhstan has a population of

Kazakhstan is a Eurasian country, bordering China and Russia, whose size is comparable to that of western Europe. Kazakhstan has a population of  In most developing countries, the majority of children do not finish primary school. For example, only 50 percent complete fifth grade in Ghana, and less than half of them can understand a simple paragraph.

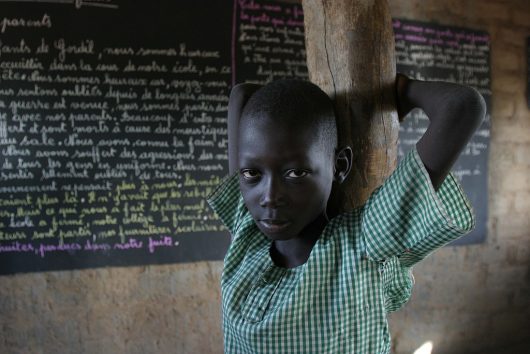

In most developing countries, the majority of children do not finish primary school. For example, only 50 percent complete fifth grade in Ghana, and less than half of them can understand a simple paragraph.

Despite its classification as a lower-middle-income nation,

Despite its classification as a lower-middle-income nation,  Reducing fertility rates in developing countries is critical for ending global poverty. Common methods of doing so include education, contraception and women’s empowerment. However, another important factor affecting fertility rates is child survival.

Reducing fertility rates in developing countries is critical for ending global poverty. Common methods of doing so include education, contraception and women’s empowerment. However, another important factor affecting fertility rates is child survival.