1. More than 1 billion people around the world live on the price of a vending machine candy bar.

Many people have only a $1.25 per day for food, medicine and shelter. Although there are 1.2 billion people living in extreme poverty, the number of people living on this amount has drastically decreased over the last three decades.

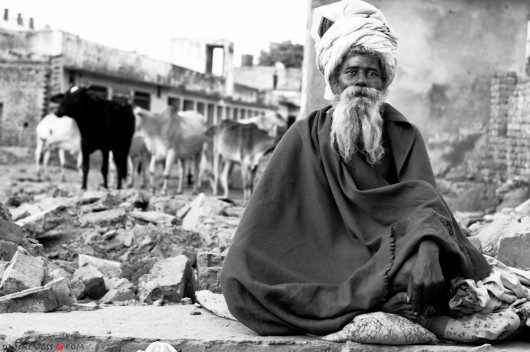

2. Poverty in India is different than poverty in China–and still different from poverty in other countries, too.

India has 179.6 million people living in poverty. India has a greater share of the world’s poor than it did 30 years ago. In the 1970s and 80s, India had about one-fifth of its people living in poverty. Now, that number has increased to one-third.

When living in poverty in India, families have to deal with many harsh conditions. Due to poor weather conditions, lack of water and misuse of insecticides, many families can’t grow the crops needed to live a sustainable lifestyle. Families suffering from these poor conditions may move to the slums of Mumbai to get away, where they face other harsh conditions like overcrowded communal bathroom facilities and the lack of proper sewage systems, meaning much of the water they consume is contaminated.

Many residents in India living in poorer conditions have put off things like health and education to keep on basic survival necessities. According to the World Bank, more than 70 percent of the 22 million people living in Mumbai live in the slums.

China, however, has 137.6 million people living in impoverished conditions. Poverty in China differs from poverty in India in that, as of August 2015, it had wiped out the majority of its poverty, but there are still people living in poverty in China’s rural regions. Between 50 and 55 percent of its people live in rural areas.

Over the last decade, the number of females has drastically increased as much of the male population has left to urban areas to find work. This has caused a decrease in farming knowledge among the general population. Farmers are also victims of devastating natural disasters that result in unpaved roads, decreased farm sizes and depleted resources.

3. There are people in the United States living in extreme poverty.

In 2012, a legislator in North Carolina stated there was no such thing as extreme poverty in the state. However, North Carolina is home to three of the top 10 poorest areas in the United States. Other areas include Nacogdoches, Texas; Dalton, Georgia and Gallup, New Mexico.

Over the last few years, the number of women living in extreme poverty in the United States increased from 5.9 percent to 6.3 percent from 2009 to 2010, meaning there are 42 million — about one in three — women living in or on the brink of poverty. One of every six of these women is elderly. In 2010 alone, more than 7.2 million women fell into extreme poverty.

4. More than enough food is produced in the world to keep everyone healthy.

Enough food in the world is produced to keep everyone on an adequate diet, but nearly 854 million people, or one in seven people, go hungry. About 2.8 million people still rely on wood, crop waste and other biomass to heat and cook their food, which can also lead to malnutrition. Luckily, there are many organizations, like Stop Hunger Now and World Hunger Organization, fighting hunger.

5. Poverty in Africa is caused by different effects than poverty in Latin America.

One of the major causes of poverty in Africa is unsustainable agriculture. Poverty in Africa takes place primarily in Africa’s rural regions, where citizens rely heavily on agriculture for sustenance and income. When the weather is harsh on crops, poor agricultural techniques are practiced or soil erosion prevents hearty crops, and many families suffer because of it.

In Latin America, one of the major causes is the inequality of wealth distribution. While poverty in Africa is mostly in rural areas, poverty in Latin America plagues both rural and urban regions. Other causes of poverty in Latin and South America are internal conflicts and issues with structural adjustments.

– Julia Hettiger

Sources: Mic, Gabriel Project Mumbai, The Guardian, Yahoo

Photo: Flickr

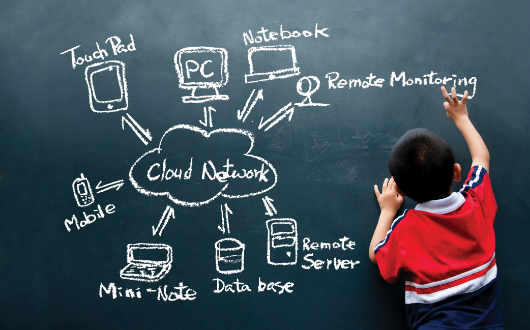

President Obama announces the launch of the Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative, or YLAI — to foster business, social, technological and entrepreneurial partnerships between youth in Latin America and the Caribbean and the United States — with the first round of participants beginning in 2016.

President Obama announces the launch of the Young Leaders of the Americas Initiative, or YLAI — to foster business, social, technological and entrepreneurial partnerships between youth in Latin America and the Caribbean and the United States — with the first round of participants beginning in 2016.