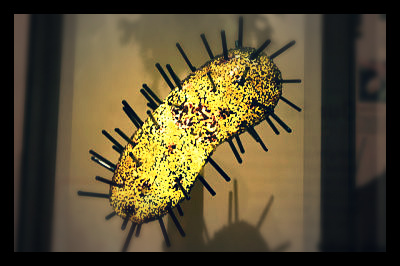

Among neglected tropical diseases, few are harder to pronounce than Schistosomiasis, a parasitic infection spread through fresh water. Fewer still are more deadly. According to the Center for Disease Control, “In terms of impact, this disease is second only to malaria as the most devastating parasitic disease.” Currently, Schistosomiasis infects more than 200 million people worldwide.

Found mostly in Africa and parts of South America and Asia, Schistosomiasis, or bilharzia, is quite an unpleasant disease. It spreads through parasitic blood flukes, also known as schistosomes, which live in certain types of fresh water snails. These schistosomes are tricky creatures and infect their victims with their larvae simply through skin contact in contaminated fresh water.

Once inside the victim’s body, the larval schistosomes mature over the course of several weeks into adult flatworms. These worms then make their way to the victim’s blood vessels where they reach full maturity and mate, producing eggs. The eggs then exit the body through the victim’s urine and stools. From there, the cycle begins again.

Oddly enough, it is not the worms themselves that cause problems but the body’s reaction to the eggs. On their way out of the body, many of the eggs become stuck in the intestine and bladder, which leads to inflammation and scarring of vital organs.

While the short-term symptoms of bilharzia are similar to that of the flu, its long term effects cause much more damage. Chronic bilharzia can cause bladder cancer, infertility and the enlargement of the liver and abdomen. It remains unknown as to how many die annually from the disease but estimates range between 20,000 and 200,000 people.

However, most victims of this neglected tropical disease continue to live for years with it. For chronic sufferers, life becomes increasingly difficult. In fact, the economic consequences of bilharzia rival its health complications. Sufferers often are too debilitated to support themselves and essentially become disabled. It has the greatest impact on children. Youth that suffer from chronic bilharzia experience stunted growth and learning difficulties, which can lead many to drop out of school. Unsurprisingly, due to its economic burden, researchers have linked instances of Schistosomiasis with poverty.

Fortunately, an effective treatment called praziquantel can rid the body of the parasite and cure the disease. Best of all, it is cheap. One treatment of praziquantel costs about 20 to 30 cents and is often available free of charge in some heavily afflicted regions of Sub-Saharan Africa. In 2012, 35 million people were treated for bilharzia with this drug.

With such a cheap and effective drug, the primary strategy of the World Health Organization (WHO) is that of mass treatment without even an individual diagnosis. These mass treatments focus on vulnerable communities like those that live and work near fresh water sources and also school children. In some areas with lower levels of transmission, many officials believe that they can eradicate this disease.

Other methods of prevention involve stopping bilharzia at its source: its freshwater snail hosts. Some efforts have aimed to focus on killing the host snails by using chemical treatments on fresh water sources. However, this has negative effects on surrounding animals and also must be continued to prevent snails from returning. Beyond medicine, the best form of prevention is simply adequate hygiene and sanitation.

While the victims of bilharzia have begun to receive more treatment, a large amount of work still remains. According to a recent WHO epidemiological record, about 40 million people received treatment for Schistosomiasis, which represents only 12.7% of the population requiring preventative treatment measures for Schistosomiasis globally. With medicine so effective, it is tragic that so many should go untreated.

– Andrew Logan

Sources: CDC, The End Fund, NCBI, WHO 1, WHO 2

Photo: Carter Center

United Nations Secretary, General Ban Ki-moon, arrived in Hispaniola this past week, with renewed promises to the Haitian people burdened with an ongoing

United Nations Secretary, General Ban Ki-moon, arrived in Hispaniola this past week, with renewed promises to the Haitian people burdened with an ongoing