Burundi is one of the least developed countries in the world, situated in central Africa between the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Rwanda. In recent years, the government has emphasized the importance of education in Burundi, making great efforts to improve both the rates and the quality of education. Here are five things you may not know about education in this often-overlooked nation.

Burundi is one of the least developed countries in the world, situated in central Africa between the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Tanzania and Rwanda. In recent years, the government has emphasized the importance of education in Burundi, making great efforts to improve both the rates and the quality of education. Here are five things you may not know about education in this often-overlooked nation.

Formal and Non-Formal Education

In Burundi, there are two types of education: formal and non-formal. Formal education, which is aimed at all children, has five levels. These include:

- Preschool

- Basic

- Post-basic

- Trades and vocational training

- Higher Education

Non-formal education consists of general activities and learning aimed at out-of-school children and illiterate adults. Primarily funded by NGOs and religious groups, this form of education focuses on providing learning in basic literacy and mathematics to make general education more accessible.

Education is Free

Part of the success of education in Burundi is owed to the widespread governmental support, evident in the decision to make education free and compulsory for all at the primary level. Consequently, an impressive 96% of children were attending school in 2011, compared to 59% just six years earlier. A U.N. Secretary-General report also stated that despite being one of the world’s least developed countries, Burundi ranked highest among countries “having made the greatest strides in education.”

Burundi Scores Highly in African Literacy Rates

By making primary education free and compulsory, education in Burundi is well on the rise. As of 2017, literacy rates among young people have jumped from 62% to 88% over a decade. Consequently, Burundi has become one of the top 20 African countries for literacy, which is a huge achievement for the nation. This is largely owed to introducing Kirundi, the local language that most of the population speak, as the language of instruction during the early years of schooling, as well as hiring dedicated teachers and emphasizing the importance of education among communities.

Burundi Dedicates a Quarter of Its Budget to Education

Burundi has an extremely young and fast-growing population. With 41.5% of its population under 15, there is a constantly growing demand for teachers, school equipment and resources. As a result, the country has invested 25% of its national budget into education for the last five years, which is significantly more than average for a sub-Saharan country. Such investment aims to increase education rates among the younger generation and keep up with the expected growing demand for Technical and Vocational Education and Training (TVET), which is predicted to increase by almost 50% by 2030.

Despite All, There Remain High Drop-Out Rates

Despite all of the efforts to improve education in Burundi, the nation continues to see high drop-out rates. According to a study conducted by the Education Policy and Data Center in 2010, school participation rates remained high for both sexes at the age of 10, with 92%. However, these rates declined to 65% for girls and 77% for boys by the time they reached 15.

More girls are dropping out than boys in their adolescent years for various reasons, such as teenage pregnancy and a lack of separate toilet facilities, which are increasingly important for girls when they begin menstruation. External factors and circumstances continue to be capable of impacting a child’s education despite the quality of schooling that may be available to them.

The Future

The above facts demonstrate the significant progress education in Burundi has seen in the last couple of decades and the areas that may still need some further attention. Despite being one of the poorest countries in the world today, Burundi remarkably achieves high literacy rates, provides free primary education and ensures that practically all children receive a basic education. Although external and societal factors remain a pressing issue and a reason for significant drop-out rates among older children, Burundi is no doubt on the right path to a brighter and more educated future for its population.

– Rose Williams

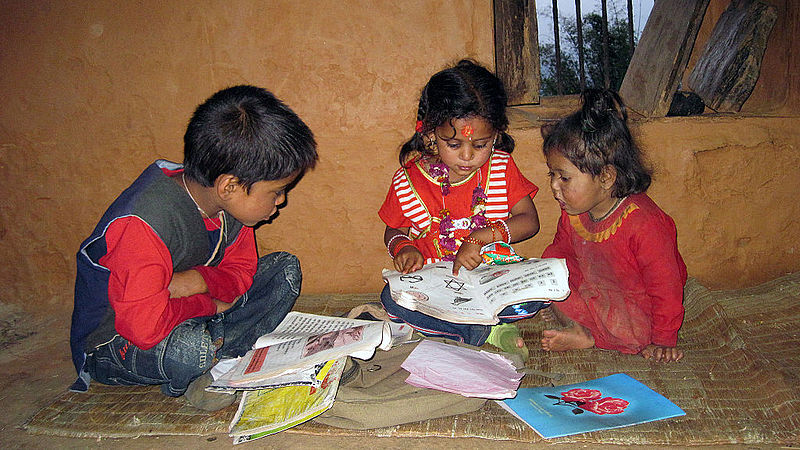

Photo: Flickr

Afghanistan’s Sesame Street is debuting its first Afghan Muppet character, who just happens to be a girl.

Afghanistan’s Sesame Street is debuting its first Afghan Muppet character, who just happens to be a girl.